One of the most important Norse myths is Ragnarok, which tells of a terrible battle at the end of the world. In this myth, the gods Odin, Thor, Freyr, Tyr, and Heimdalr battle against Loki and Fenrir the Wolf, who have burst free, aided by Jormungand the Serpent, Hrim the Giant and Surt in the plane of Vigrid outside Asgard. The gods are reinforced by 800 Einherjar from Valhalla, with the enemies in turn having Surt’s fire demons, Hrim’s giants, and Naglfar, the ghastly ship made of the nails of the dead. Odin greets Fenrir with cold sheer, and Thor beside him looks to settle his old score with Jormungand. Freyr is killed by Surt, and Tyr and Garm the Hound kill each other, with Heimdalr and Loki doing the same. The Serpent proves a match for the Thundered, and although Thor bests Jormungandr in the end, he is able to step back only nine paces before dying from the serpent’s poison. Odin is eaten by Fenrir, but Vidar avenges his father and kills the wolf by ripping its jaw apart with his feet. Surt casts his fire through the nine worlds and destroys everything (Leeming 82). But the earth rises from the deeps again one day, with Lif and Lifthrasir surviving to renew the race of man (Leeming 83). This myth shows how the world will not last forever and that eventually, it will come to an end. However, it will later be reborn again in a better state. The Norse deities in the myth have inspired many artifacts over the years, both from the Norse people themselves and from later Northern and Western European cultures up to the modern day. There is a stone cross, or runestone called Thorwald’s Cross depicting the scene from Odin’s death in Ragnarok, and it shows a syncretism between Norse mythology and Christianity.

Thorwald’s Cross was found in the church Andreas which is in the Isle of Man. Rundata dates the runestone to the year 940 (Olsen). At the same time, Pluskowski dates it to the 11th century (Pluskowski 158). The stone’s maker is written as Thorvald, with this being the only inscription remaining from the message which is inscribed on the cross. The cross is part of the Manx runestones, a group of runestones from the Viking Age found across the Isle of Man. In 1983 there were 26 surviving stones on the island, compared to 33 in all of Norway. It is possible that so many of these stones appear on the Isle of Man due to the combination of the Norse runestone tradition with the Celtic tradition of stone crosses (Page 227). The church also contributed by not condemning the runestones as pagan, but instead allowing the recording of the people who created the crosses for Christian purposes. The crosses tell the story of the conversion of the Manx Norsemen to Christianity and the gradual process through which they achieved it. They show a process of syncretism between the old Norse gods and the new Christian faith, along with the coming together of both the native Celtic Manx and Norsemen. The stone crosses are testament of a sophisticated society with skilled sculptors (Mackie).

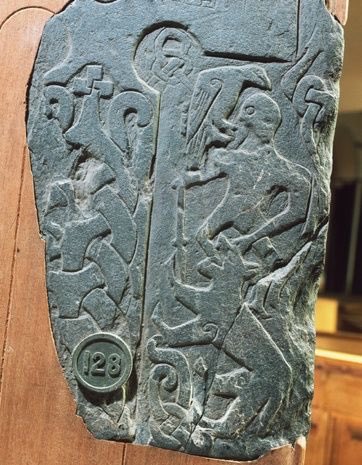

Although the cross is badly damaged, there is enough on it to piece together its story. On one side of the stone there is a depiction of the Norse god Odin being devoured by the wolf Fenrir. A raven is perched on Odin’s shoulder, while the wolf is below him and devouring his leg (Pluskowski 158). According to Andy Orchard, the raven perched on Odin’s shoulder may be either Huginn or Munnin, Odin’s ravens (Orchard 115). Next to this image is a large cross, and on the other side of the stone there is a depiction of Christian symbolism- a figure with a book and cross, by a fish and a defeated serpent (Manx Museum). The Christian part of the stone has been described as Jesus fighting Satan (Hunter and Ralston). It is syncretic art, combining Christian and pagan beliefs. The runestone’s symbolism, with Ragnarok on one side and the triumph of Christianity on the other, can be interpreted as the shedding and defeat of the old pagan gods, to be replaced by the new Christian faith. The parallelism between the Norse and Christian parts of the cross are shown with Odin fighting Fenrir and Jesus fighting Satan, although Odin dies while Jesus triumphs against Satan. It also points to the similarity between the end of the world in both Norse mythology and Christianity, with a terrible battle taking place in both but the world being reborn or resurrected in a better state. It also shows that even through the Norse eventually did convert to Christianity, it was a gradual process that was aided by syncretism with their own native religion. Artifacts like this likely made it easier for the native Norse population to accept the new Christian faith, as they would have already been very familiar with the myths of their own culture.

In conclusion, the myth of Ragnarok remains one of the most key stories in Norse mythology and has been passed down through the ages in different forms not just in artifacts from the period, but also books, paintings, movies and video games. Even in the modern day, this myth holds important lessons. It tells about how all things must and will come to an end one day, but that there will also be rebirth in a better world. Another message from this myth is that death is not the end.

Works Cited

Hunter, John and Ian Ralston. The Archaeology of Britain: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 1999.

Leeming, David A. The World of Myth: An Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Mackie, Catriona. Isle of Man Government – The Manx Crosses and the Scandinavian Settlement of the Island. 13 February 2018. 3 February 2019.

Manx Museum. BBC – A History of the World – Object: Thorwald’s Cross. 13 January 2010. 4 February 2019.

Olsen, Br. “Rundata 2.0.” n.d.

Orchard, Andy. Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell, 1997.

Page, R. I. “The Manx Rune-stones.” Runes and Runic Inscriptions (1983): 227.

Pluskowski, Aleks. “Apocalyptic Monsters: Animal Inspirations for the Iconography of Medieval Northern Devourers.” The Monstrous Middle Ages (2004): 158.

Leave a comment