Genealogical Relations of Manx

Manx is a Celtic Language, a member of the Goidelic branch of the Insular group of the Celtic language family, which in turn is a member of the wider Indo-European language family. Languages related to it include Irish from Ulster and Scottish Gaelic of Galloway, however it has different spelling protocols. The languages have large degrees of mutual intelligibility. Manx’s distant relatives include Welsh, Cornish and Breton, which shape the Brythonic languages. All Celtic languages share similar grammatical structures although with relatively little common vocabulary (Omniglot, n.d.).

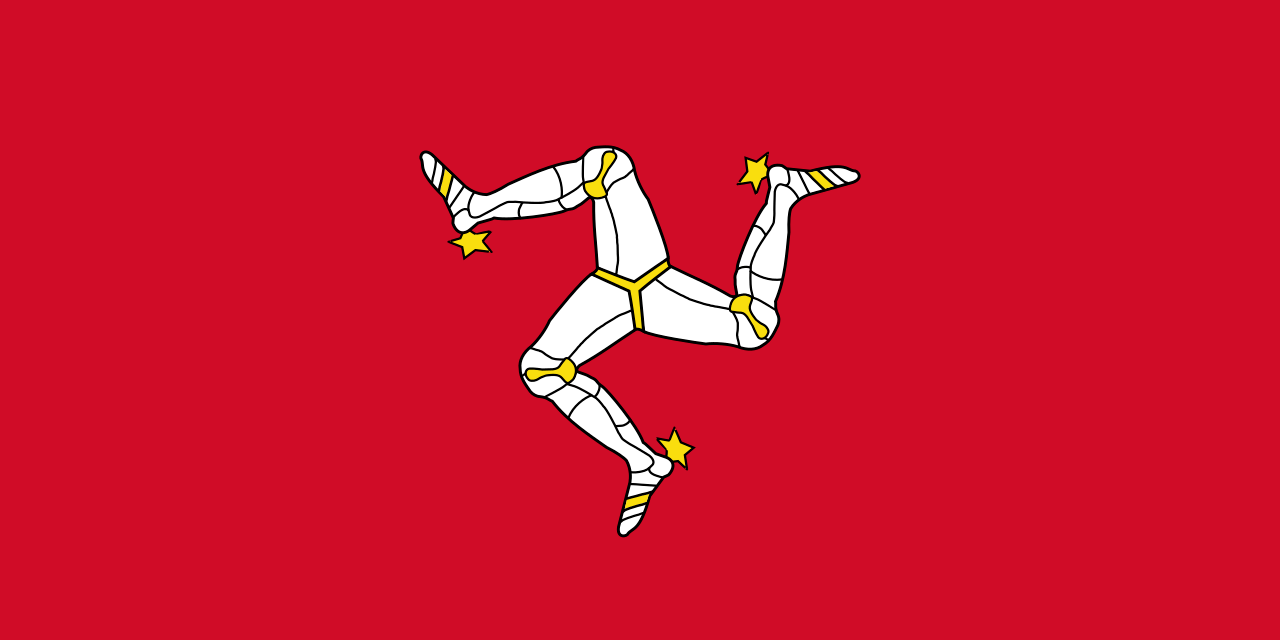

Isle of Man & Manx people

Manx is spoken on the Isle of Man, which is located on the Irish Sea off the northern coast of England and roughly equidistant between England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Rather than being part of the UK, the island is a crown possession which is self-governing under the British Home Office’s Supervision (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019). The island’s population is 83,314 and the capital city is Douglas. The island has a central mountain mass culminating in Snaefell and extending north and south in flat agricultural land. Its coastline is rocky with cliffs. Due to action during various glacial periods, the grass-covered slate peaks of the central massif are smooth and rounded. The island is treeless except in sheltered places. It has a maritime temperate climate with cool summers and mild winters (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019). The Manx people are a Celtic group closely related to the inhabitants of Ireland and Scotland and are considered one of the 6 Celtic Nations. and have been on the island since at least the 4th century AD. However, they also have significant Norse and English influences due to being controlled by those places. They are predominantly Protestant Christians, with the majority belonging to the Methodist sect. Most Manx speak English (Minahan, 2000, p. 453).

Historical Development of Manx

Irish monks and merchants brought their Gaelic language to the Isle of Man in the 4th to 5th centuries AD during the spread of Christianity in the British Isles. They founded clerical settlements and put up stones with ogham inscriptions, replacing the earlier Brythonnic language with Gaelic. The island was later invaded by the Vikings who formed a kingdom centered on it and extending to the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland. But their impact on Manx was minimal due to their rapid assimilation. Manx started to surface as a distinct language with the death of the last King of Mann in 1265 and subsequent Scottish control. Control of the island was shuffled between England and Scotland until in 1405 King Henry IV gave it to Sir John Stanley, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, beginning English control. Manx was an unwritten language for much of its history as English and Latin were used for official documentation (Murphy, 2018). The earliest record of Manx is a translated version of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer from 1610, done by a Welsh bishop who used a writing system similar to that of English (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013; Greene, 2017). The first book was published in 1707 (Murphy, 2018). Manx was spoken by nearly the island’s entire population until the 1765 Revestment Act when the Duke of Atholl sold the entire island to the British Crown (Omniglot, n.d.).

The Decline of Manx

Manx later dwindled due to many factors. The Anglican Church withdrew its support for Manx teaching in schools, and by 1782 only five schools on the island did not have English as a language of instruction (Ager, 2009, p. 16). The island’s economy also collapsed and later large-scale emigration from the poor areas where Manx was strongest occurred. This was coupled with further immigration from Northwest England during the later 18th and early 19th centuries (Omniglot, n.d.). But tourism impacted the Manx language the biggest, beginning in 1833 when a regular ferry service between the Isle of Man and England was established. In order to succeed in the tourist industry, it was necessary to speak English, as Manx was seen as a primitive and ignorant language (Ager, 2009, p. 18). The death of Manx created households where grandparents only spoke Manx, parents spoke both English and Manx, and the children spoke only Manx (Murphy, 2018). Manx only survived in some remote villages and farms. In 1871 a survey revealed that outside the capital of Douglas 12,340 people, or 29% of the population, habitually spoke Manx. Just 4.6% of the Isle of Man’s population spoke Manx by 1911 (Ager, 2009, p. 20). Just 2 native speakers of Manx remained by the 1960s: Sage Kinvig and Edward Madrell. After the latter’s death the language was declared extinct although a few Manx speakers remained until the 1980s (Omniglot, n.d.).

Preservation of Manx

However, efforts to preserve and teach Manx have been around since the 19th century, when many dictionaries, grammars and other books in the language were published, including a grammar of Manx in 1804 by the Reverend John Kelly, along with a dictionary published in 1866 after he died (Ager, 2009, p. 22). The Manx Society published a number of works in and about Manx between 1858 and 1907, including Bishop John Phillip’s Manx translated version of the Book of Common Prayer. 1899 saw the founding of the Manx Language Society, which sought to preserve the language and encourage interest in it (Ager, 2009, p. 23). In the late 1930s and 1940s a small group of Manx admirers spoke and recorded Manx as much as possible (Ager, 2009, p. 27). Interest in Manx increased and by 1971 there was a 72% rise in Manx speakers (Ager, 2009, p. 28). In 1985 the Isle of Man’s government gave Manx limited recognition (Ager, 2009, p. 24). Since 1991 Manx has been taught in Manx schools. Since 2001 Manx playgroups and a primary school have opened, one secondary school has some lessons in Manx, and Manx language classes for adults have taken off. Content such as songs, stories, radio programmes, and videos continue to be created in Manx. In the 2011 Isle of Man census, 1,823 people claimed to be able to speak the language (Omniglot, n.d.). However, it is considered “critically endangered” by UNESCO (Whitehead, 2015).

Key features of Manx & words/phrases

The use of an orthography based on English in the first book written in Manx makes it difficult for readers of Irish and Scottish Gaelic to understand although they are interested in it due to it being a dialect completely free of literary influences. Soon the orthography was fixed, and a profound succession of later phonetic changes made Manx’s written form an inaccurate representative of the final stages of the language. Manx shares more phonological similarities with eastern dialects of Irish than Scottish Gaelic but has more common morphology and syntax with that of Scottish Gaelic, likely due to the shared British foundation. It has a similar tense system to Scottish Gaelic and Welsh, and its use of circumlocutory verb forms, or longer forms with several elements, with the auxiliary meaning “to do” going farther than either languages, particularly in its final stages (Greene, Celtic languages – Scottish Gaelic, 2017). “Good morning” in Manx is “Moghrey mie”. “Good afternoon” & “Good evening” are both “Fastyr mie”. “Good night” is “Oie Vie”. “What’s your name” is “Cre’n ennym t’ort?” in the singular and Cre’n ennym t’erriu?”. “Do you speak Manx?” is “Vel Gaelg Ayd?” (Omniglot, n.d.)

Bibliography

Ager, S. (2009). A study of language death and revivalwith a particular focus on Manx Gaelic. Retrieved from Academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/1989844/A_study_of_language_death_and_revival_with_a_particular_focus_on_Manx_Gaelic

Greene, D. (2017, April 18). Celtic languages – Scottish Gaelic. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Celtic-languages/Scottish-Gaelic

Greene, D. (2017, April 18). Celtic Languages – Scottish Gaelic. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Celtic-languages/Scottish-Gaelic

Minahan, J. (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Murphy, K. (2018, August 6). A Very Brief History of the Manx Language. Retrieved from History Today: https://www.historytoday.com/history-matters/very-brief-history-manx-language

Omniglot. (n.d.). Manx language, alphabet and pronounciation. Retrieved from Omniglot: https://www.omniglot.com/writing/manx.htm

Omniglot. (n.d.). Useful Manx Phrases. Retrieved from Omniglot: https://www.omniglot.com/language/phrases/manx.php

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2013, October 25). Manx language. Retrieved from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Manx-language

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2019, September 13). Isle of Man | History, Geography, Facts and Points of Interest. Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Isle-of-Man

Whitehead, S. (2015, April 2). How the Manx language came back from the dead. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/apr/02/how-manx-language-came-back-from-dead-isle-of-man

Leave a comment