Canada entered the 20th century with indefinite wealth and advancement. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s government continued building the railway and by 1914 it reached both coasts. While diplomatic relationships began to form with the rest of the world Britain directed most of Canada’s international relationships, and Canadians started to get sick of being beholden to a small island thousands of miles away.

Yet more resentment flared up due to a situation in Alaska. To solve a disagreement between the US and Canada over the Alaska/Yukon border a delegation of three Americans, three Canadians and one British minister was created. The Americans brought forward a proposal that was mostly favorable to them. The Briton Lord Alvertone voted for this, which Canada saw as a betrayal to their own interests and more proof of British double-dealing.

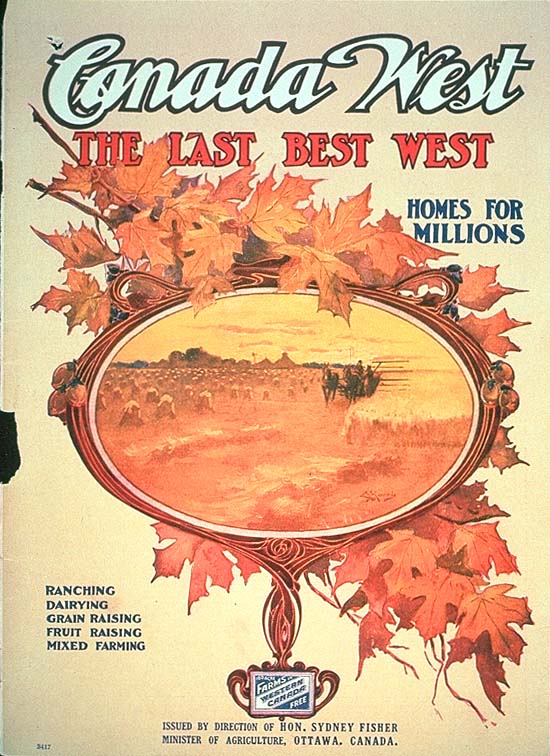

Britain also supplied the growing inflow of Europeans. Canada preferred British immigrants, but the Canadian government was not satisfied with the number of people coming in and wanted more. The West especially had large swaths of vacant lands. Laurier’s Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton, changed immigration policy and started a large marketing plan intending for other European settlers to go to the Prairies. Advertisements saying:

The Last Best West

Homes for Millions

160 Acre Farms in Western Canada

Free

were produced and brought into circulation throughout Europe in a dozen languages. As a result, Ukrainians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Hungarians and Serbs headed to Alberta and Saskatchewan (provinces formed in 1905) in large numbers. Sifton thought that the farming backgrounds of Slavic immigrants suited them well for the west, When other government officials criticized Sifton for allowing “inferior breeds” into Canada, Sifton responded: “I think a stalwart peasant in a sheep-skin coat… with a stout wife and half a dozen children, is good quality.”

For a small cost of $10 (for registration) and a vow to stay on the farm for six months of the year for three successive years, immigrants were given 160 acres of harsh but gratis prairie land and the chance to work a farm.

The prairie settlers faced starting challenges similar to the French habitants. The thick Prairie brush had to be removed to plant crops and to stop the damaging grass blazes. Soil, which a burning sun had dried for thousands of years, needed to be plowed with horses and oxen (the Doukhobors, a Christian denomination oppressed in Czarist Russia, harnessed women to their plows). Winters with harsh snowstorms and temperatures cold enough to freeze human tissue within five seconds, and scorching summers frequently lacking rain, were complications only balanced out by successful harvests. Many people withdrew from the west’s hardships searching for a more lenient setting as prairie folk tunes frequently described:

So farewell to Alberta,

farewell to the West

It’s backward I’ll go

to the girl I love best

I’ll go back to the east

and get me a wife

And never eat cornbread

the rest of my life.

The harsh toils and survival of prairie farmers helped give rise to Canada’s special type of democratic socialism. The origins of populist, reformist and progressive developments in Canadian politics can be traced to this period.

Women also had input. Nellie McClung and Emily Murphy spearheaded a campaign in the renowned “Persons Case”. The frontier women criticized the androcentric reading of the British North America Act’s “persons clause” which stated that “persons” could be appointed to the Senate. Canadian parliament saw this as meaning only men.

The Supreme Court rejected McClung’s and Murphy’s petition but its choice was reversed by the Privy Council in London. This allowed women to join the Senate in 1929.

Growing industrialism: The arduous west was not the sole place with challenges. New businesses and industries were created and grew causing drastic shifts in the lives of several Canadians: commercial growth brought wealth to the entrepreneurs, but several others faced toil and were taken advantage of. The factories of the east turned into the harsh setting for urban immigrants. But in contrast to the prairie farmers, factory laborers were seldom provided with chances for advancement and were constrained.

Early Canadian entrepreneurs infamously took advantage of work from migrants. It was usual procedure to provide them with 10-12 hour days, 6-day weeks, and meagre wages. It was also usual to hire women and children with less pay. Poor labor situations and harsh punishments worsened what were already difficult lives for workers.

When a Labor Commission confronted a Montreal merchant in 1910 over his harsh flogging of six year old girls in his textile factory, he responded that just as dogs needed to be strongly disciplined, so did hired children. In 1905 David Kissam Young, who wrote for the Industrial Banner, expressed the principles of the Canadian factory boss as: “Suffer little children to come unto me; For they pay a bigger profit than men you see.”

This ended up leading to the creation of trade unions and labor groups. In 1908 Ontario enacted Canada’s first child labor law – only people at least 14 years old could be hired.

World War I: Canada was strongly affected by the dilemma which originated in the Balkan States and drew most of Europe into war. Still seen as a loyal part of the British Empire, Canada saw that it had a duty to join the war supporting England.

This choice had benefits for Canada. It turned into the main agricultural market of Britain and its allies after Russian wheat exports were disrupted by the war. Canadian materiel industries were created immediately and riches were reaped. But the price paid was many lives.

Robert Borden served as Canada’s Prime Minister during the war, and his primary job was to find the 500,000 fighters he had promised Britain. Canadian society started to be influenced by attempts to strongly support the European war. Political leaders promoted civic pride, priests spoke of Christian obligations, army officers advertised flashy highland clothing, and women sported badges saying “Knit or Fight”.

Criterion for army admission was expanded: the young, old, and disabled were recruited. As the war continued and the requirement for more troops grew, the Canadian army shifted its ethnic polities to enlist Indian, Japanese and black Canadians. But there were still insufficient troops by 1916 and the Prime Minister naturally looked to Quebec.

French Canadians in Quebec did not want to contribute to the war. They did not see themselves as owing anything to either France or Britain (as both had not treated the Quebecois too well), and Quebecois had disillusioned reactions to the government’s nationalist propaganda. When conscription began to be seriously considered in Canada’s parliament, French Canadians faced mandatory recruitment into the army. Frictions in Quebec culminated with riots protesting conscription in 1918. In one confrontation, soldiers brought from Toronto shot at the crowds, killing four civilians. The government threatened to immediately conscript future rioters.

Borden’s cabinet started to take stricter measures. A War Tax Measure, straining household budgets with already risky balances, was enacted; anti-loafing laws (meaning that any males between 16 and 60 years old who were not profitably working would be imprisoned) was implemented; all “radical” unions were repressed, and all publications written in enemy tongues were banned.

But on August 18, 1918, Canadian and Australian soldiers pushed past a German regiment close to Amiens. The German troops were driven farther back until their final loss at Mons on November 11, 1918. When it had all ended, 60,611 Canadians had been killed – and thousands more suffered agonizing and irreparable mutilations, both in body and mind.

Canada’s roaring twenties: Canada had similar developments to the roaring twenties of America, but they were less intense. In America an Inquisition-like movement called the Big Red Scare spread around the nation pursuing any “suspected or real communists” (including African Americans, Jews and Catholics). This campaign did not penetrate strongly into Canada, dismaying the American Ku Klux Klan which counted 6 million members. Radical parties in the prairies, union bosses and the small amount of confessed communist provokers faced mild to strong harrying.

But generally, Canada did not respond towards “dissent” with the United States’ zealous fealty to “democracy”.

Both Canadians and Americans were enraptured by the the alluring Toronto-born Mary Pickford and headed to watch the newest silent movies of Douglas Fairbanks and Rudolph Valentino: women wore far less pounds of clothing, got haircuts, and campaigned for new gender identities. Canadians respectfully admired Babe Ruth’s athletic talents… but Canada remained a country of small towns. This gave it a small town conservative outlook – which was put into literature with Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches (1914) – subtly boastful but simultaneously self-reproaching.

Canada took new paths too early in the century. The artists of the Group of Seven produced an impressive but disreputably unique visual picture of Canada’s landscape. Adopting Impressionist, Cezanne, and Art Nouveau procedures, Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald, Franz Thompson and Frederick Varley re-examined Canada as daring mavericks – their projects brought Canada acclaim across the world and would continue to influence the nation’s visual arts for several years.

The 1920s appeared to be prosperous years for Canada despite 1923 and 1928 having declines in the agricultural market. No one could have predicted October 1929’s calamitous Wall Street crash.

The Depression in Canada: The breakdown of the international grain market worsened the Depression – due to a wheat surplus it was cheaper for Canada’s customers to buy supplies from Argentina, the USSR or Australia. The circumstances had turned extreme by 1929. The depression hit Canada harshly.

The Conservative government of R.B. Bennett mobilized fast to deal with the troubles of a stalling economy. They started up relief plans and social services (which became adept at finding “fraud and waste”). Someone could lose the right to relief aid by owning extravagant objects like ornaments, jewelry, pets, cars, and telephones.

Canadian politicians, insensitive in their failure to understand the difficulties brought about by the Depression, insisted that jobs were available to be taken, and they started workcamps for single men in British Columbia. On their way to find work, hundreds of laborers died from freezing on the trains or were murdered. The men who reached the camps earned 20 cents daily for their efforts.

Men and women were driven to the streets by large-scale unemployment. In Toronto a group of men earned a meagre 5 cents for spending seven hours clearing snow from the driveway of a rich Rosedale family. Women contended for the most undignified domestic work and relied on the goodwill of their employers for a tolerable wage.

But the prairies saw the most hardship. Out west it appeared as if the power of nature had worked together with the economy’s fluctuations to bring as much hopelessness as they could. In 1931 the fertile topsoil was swept away by the strong winds; in 1932 a grasshopper plague ate up the crops, and in 1933 a succession of droughts, frozen rain and early cold snaps began.

Even Newfoundland delivered dried cod cakes to prairie families, despite hardly getting by themselves. The struggles of the prairie during the Depression helped give rise to the creation of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), a farmers’ labor organization that would then turn into the socialist NDP (New Democratic Party).

As the Depression worsened across Canada, radio sets started to serve as the primary escape and the Canadian Radio Broadcast Commission was created in what the government said was an effort to lessen the distress of millions. Many Canadians were given much needed distractions by professional sports events, Gordon Sinclair’s energetic reports, and the announcing of occurrences such as the birth of the Dionne quintuplets in Calendar, Ontario. Families could overlook their problems for an hour or an evening.

When the Depression eventually concluded, it left a mark on millions of Canadians – a difficult decade had created a prudent generation.

World War II: The headline of one prominent Canadian newspaper said “WOUNDED FATHER AND SON ROUT THREE GUNMEN” just five days prior to Britain’s declaration of War against Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. Nothing could be found on Hitler’s annexation of Czechoslovakia, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between the Germans and the Soviets, or the invasion of Poland. The Star’s headline showed the Canadian public’s mood towards war: that it would simply go away. The World War I veteran Angus MacDonald said of Canadians: “We all longed for peace. Everybody. Some longed so deeply that they came to believe that never again would there be a war”. The scars from the last war had still not healed.

Even Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King though that Hitler was simply a “simple peasant” who did not wish to initiate a fight with either the UK or France. But on September 3, 1945, Canadians were given a rude awakening. The newspaper headlines now said: “BRITISH EMPIRE AT WAR – HIS MAJESTY CALLS TO BRITONS AT HOME AND OVERSEAS.”

Canada’s participation in the war was complicated by the 1931 Statue of Westminster which had turned it into a self-governing, equal realm within the British Empire. Legally Canada did not have to join the war – but Canada’s loyalty to Britain meant that, in its mind, it had to help Britain, and rightly promised to do so.

French-Canadian objections: Like in the preceding war, the French Canadians objected to the government speaking for all of Canada’s people, and these feelings were echoed by the politician Maurice Duplessis. Duplessis advocated that Quebec stay out of any European War. Then, the German Blitzkrieg started in the spring of 1940, attacking Norway and Denmark before Britain was forced to retreat from the beaches of Dunkirk by June 4, and less than a week later France sought a ceasefire with Germany.

In Canada Duplessis’ arguments for neutrality were rejected as a “total war” passion swept the country and many French Canadians joined overseas service.

Prime Minister Mackenzie King promised Canadians that he would never force conscription upon them as long as his Liberal government stayed in power, and this helped keep support for the war. Due to this, Canada smoothly transitioned into a wartime economy. Essential goods were limited and commercial businesses were directed to war manufacturing. Before long Canada was spending $12 million daily on the war effort and more than 1.5 million citizens worked in munitions factories by 1943.

Because of the increasing ties between itself and the USA, Canada immediately declared war on Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941.

As the war violently continued, Britain started to have serious manpower issues and conscription appeared to be on the horizon once again. Under growing stress, Mackenzie considered a national plebiscite to determine if the Canadian people would allow the government to conscript them.

The voters said yes, but most Quebecois said no. As a result, Quebec saw the rise of a passionate nationalist campaign to counter the draft; one of its members was the young Pierre Elliott Trudeau, the future Prime Minister. But thankfully for King, conscription was not required until the war’s last months.

When the war had concluded, 45,000 Canadians had died. The troops had fought courageously and honorably and had contributed strongly to many of the war’s key battles.

But sadly there were some black marks on Canada’s record like in other countries. Using the justification of irate neighbors possibly harming Japanese Canadians, the Canadian government placed 15,000 of them in internment camps and sold off their property.

Canada, under the Minister of Justice Ernest Lapointe, rejected all but a few Jewish refugees escaping Hitler’s concentration camps, both when the war was occurring and after. Lapointe’s “none is too many” opinions received massive approval from prominent anti-Semites around the nation.

With these stains in its record, and with unsettled and exhausted soldiers returning, Canada started the challenging endeavor of constructing a new future.

Leave a comment