The document is a copy of a letter that Augustus had given in reply to Samos, inscribed in a marble block from the grand archive wall of the theatre in Aphrodisias, Caria. The date of the letter is not exactly clear: but it was most likely from soon after 27 BC.[1] The Aphrodisian copy may have been from the 3rd century AD.[2] This copy was usually transliterated as “Sebastos”, the Greek translation of “Augustus”, so it may have been added at Aphrodisias sometime after the document had been known in the city. The Samians had requested the privilege of freedom from Augustus, but he refused their request. He pointed out that he had only given freedom to the Aphrodisians because they had taken his side in the war and due to their goodwill were made captives. Augustus could only give the greatest privilege if he had a good reason, and while he was sympathetic towards Samos, especially due to his wife Livia’s influence, he would not break his custom. Livia had past links with Samos.[3] The intended audience was the Samians, likely the city’s assembly of the demos which sent the original letter. However, this letter likely spilled out into the general public as evidenced by Aphrodisias evidently becoming aware of it.

This document was a response to a petition by the Samians for freedom, which was written below the petition following the usual procedure. The freedom that the Samians wanted was a specific political status that meant many things: the freedom to retain possessions, freedom from taxes, freedom from having to host a garrison, and freedom to use local laws. Roman freedom originally only included political independence, not these other rights. The final sentence of the text hints at this last function when Augustus’ says that he doesn’t care about the money Samos pays as tax. Rome began to adopt this idea of freedom from the Greeks in the early 2nd century. In 196 BC, Titus Quinctius Flamininus declared the freedom of the Greeks. The Romans pledged to preserve the standing of individual Greek cities if they surrendered into Roman trust or fides and stayed loyal to Rome. “Good faith” became the foundation of a mutual patron-client relationship between Rome and individual Greek cities.[4] Long before Roman provinces had been established in Greece and Asia Minor, the Romans started to provide freedom and other rights to individual cities.[5] Deditio in fidem allowed the Romans to treat the dediticii or surrendered how they pleased.[6] The Romans increasingly treated the dediticii with mercy and they could look forward to receiving freedom.[7] This idea of deditio in fidem must have been the relationship between Augustus and Aphrodisias. They were relinquished to the good faith of Rome, who gifted them freedom. The Samians are appealing to an idea that the Romans had adopted and developed over the past few centuries. As a Greek community, they were well acquainted with this idea and wanted it for their city.

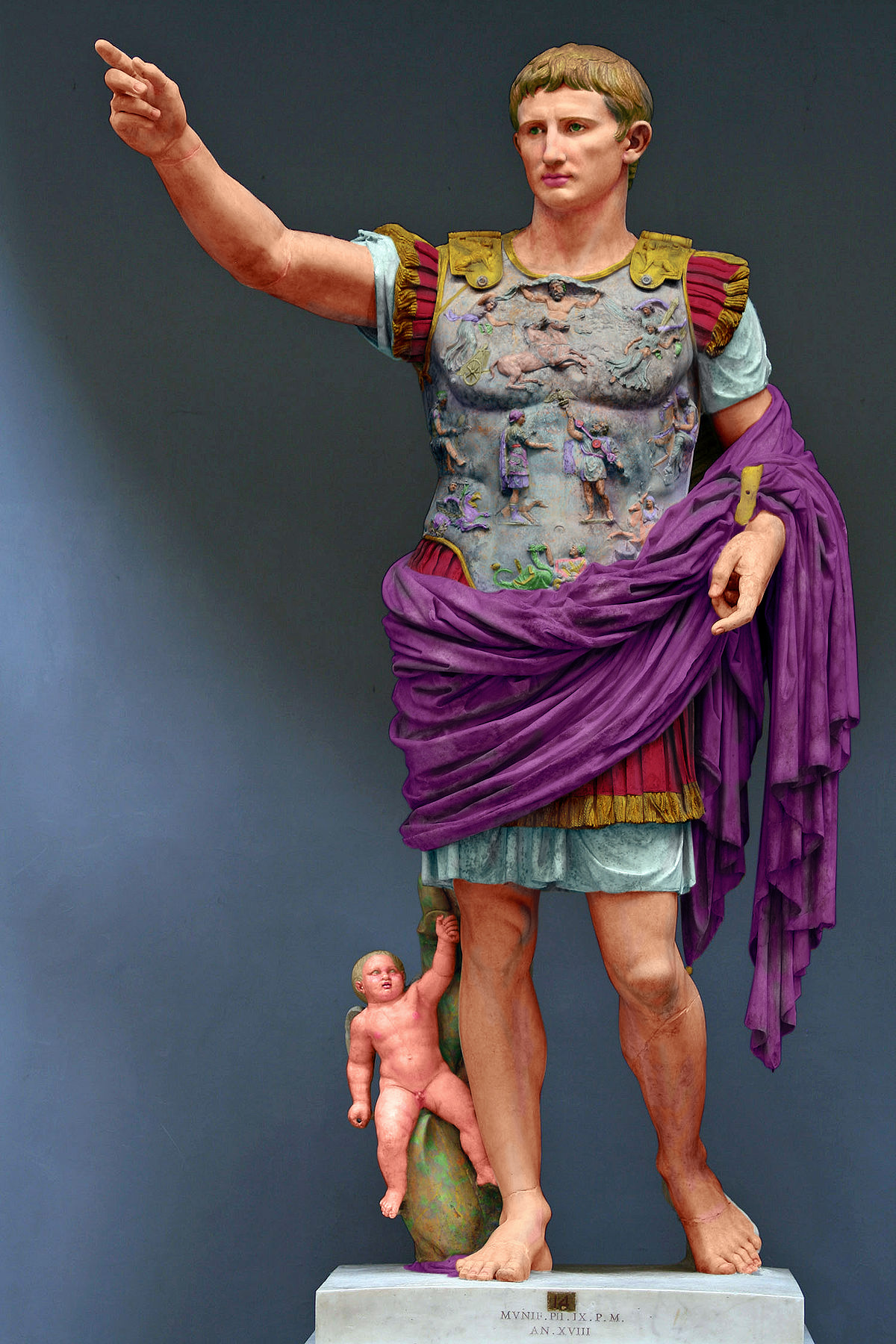

This document is mostly about its immediate surrounding. It tells us about the relationships that Augustus had with both Samos and Aphrodisias. Augustus had a close relationship with Samos and considered it one of his favorite places, as he says in his letter. After his victory at Actium, the city celebrated his victory, and Augustus went there. However, he was then forced to depart because of issues in Italy. He stayed in the winter of 30/29 when he began his fifth consulate. His wife Livia also had a good relationship with the city, as the letter mentions, and may have joined Augustus on one of his first stays on the island. Her relationship is shown by two statue bases honoring Livia in the Heraion, with the earlier one between 31 and 27 honoring her “piety towards the goddess”. Augustus shared a temple with the goddess Roma, and many statue-bases, all from 27 or later, are dedicated to both.[8]

But in the political context, Augustus’ relationship with Aphrodisas was closer and the letter explicitly tells us this. The letter tells us a bit about the recent history of the relationship, which had developed over many years. The relationship was very close since this was the only city that Augustus appears to have given freedom to, and the document tells us why Augustus was giving them freedom. Aphrodisias had been linked to Rome even before Augustus. According to its’ “Archive Wall”, many Roman Republican leaders, like Sulla and Julius Caesar, established links with the city and several of its elite families. The city of Aphrodisias had become a central Roman province in the East by the late 30s BC and was important for its military and political activities in the region.[9] The phrase “took my side” in the letter likely refers to the war with Quintus Labienus and his Parthian allies back in 40. Aphrodisias had suffered destruction during that war, so this is what Augustus most likely means when he says they “were made captives”.[10] Among Augustus’ praises of the city was its “fidelity to the Roman nation with which they had sustained the Parthian inroad”.[11] Augustus is rewarding the long sacrifices incurred by that city. A few other letters tell us about the history of Aphrodisias’ freedom. One is from Augustus (then called Octavian) to Stephanus, a local boss in the city. He proclaims the city’s freedom and mentions the freedman Zoilus, a citizen close to him. Zoilus probably requested this, but nowhere is it implied that he is the reason the city is being given its freedom. The letter, which was meant to be published, informs the city of its patron Octavian’s care. Aphrodisias is a unique haven for Octavian within Antony’s sphere of influence in Asia. Octavian did not take up his patronage of Aphrodisias before 40, and his renewed interest may be related to the city’s destruction in Labienus’ invasion. [12] Thus the letter may be dated to late 39 or early 38.[13] In the treaty of Brundisium, Octavian was allowed to retain Aphrodisias, and in return Antony got Bononia in Italy. Octavian’s relationship with Antony was still cordial, and he recommended the city to him. Stephanus may have been a freedman or a local agent. Antony was the superior of Stephanus, so Stephanus had to report to him on how well he has carried out the task Octavian ordered.[14] This document clearly shows the extent of Augustus’ special relationship with Aphrodisias, which long preceded the letter to Samos. Augustus had strong obligations to the relationship. Later, Aphrodisias would take Augustus’ side in his wars against Mark Antony.[15]

Another aspect of Aphrodisias’ importance was its status as a center of an imperial cult, which started in Augustus’ time and endured in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Because it is very general, the letter does not mention this outright, but it is important to know because it is another indication of the strength of the Roman-Aphrodisian relationship. The city had the Sebasteion, a temple and sanctuary dedicated to Augustus and the later emperors. Eastern imperial cults were long established in the Hellenistic East even before the Roman Empire. They legitimized the power and divine right of leaders like Sulla and Julius Caesar by linking them to a state pantheon. The title sebastos, meaning “holy/revered place”, the Greek equivalent for augustus, was given to the emperors in the east. Citizens in provinces were encouraged to honor the emperors. Pliny the Elder stated that Rome nurtured its lands, and this is proven not just by the strong relationship between Aphrodisias and Rome, but also the success of the city after Augustus’ ascension as emperor and the citizenship gifted to much of the Aphrodisian elite. Emperors were not honored as gods but given similar honors to the gods while still acknowledged as mortal men.[16] The combination of Roman and Hellenistic elements in the Sebasteion was an Aphrodisian innovation. Aphrodisias’ imperial cult honored the peace and stability Augustus brought to the Roman Empire from his military exploits. The Sebasteion also represented the later emperors Claudius and Nero.[17]

In this letter Augustus did not reference any limits to his power. He did not have to, as Rome was now an empire with him as its emperor. The Aphrodisian elites were flattered by Augustus’ letter, so they inscribed it along with other objects of imperial correspondence to the wall of their theatre to advertise their strong relationship with Augustus. This was one of the few examples of a negative response from an emperor surviving.[18] Aphrodisias did this hundreds of years after the event. The antiquity of that letter added to its prestige for the Aphrodisians, as it would mark them as being a long established and special city in the Empire, with its special relationship to the emperors going all the way back to Augustus, the first emperor.

Samos did not have the same close political history with Augustus or the Roman Empire. It had also been the base of Antony’s and Cleopatra’s fleet before the Battle of Actium, and the Samians had celebrated a festival thinking that their side would win. After Octavian’s victory, the Samians were afraid of being held accountable, especially because Augustus was now emperor. They must have presented the case to Octavian that they had been occupied and forced to support Antony against their will. They were also counting on Livia’s patronage. While Livia was often at Augustus’ side, she was not with him at the moment and didn’t accompany him on the campaign either. Her appeal to Samos may have been done through a letter. Augustus presented his wife Livia as a strong patron of kindness and mercy. It can be assumed that Livia’s advocacy influenced Augustus’ reply, which was a compromise: he would not punish the city because of his fondness for it and his mercy, but to ask for freedom was too much.[19] The emperor acted autocratically in denying Samos’ request. As he says in his letter, he does not care so much about the taxes that Samos pays as he does about having a good reason to give them freedom. After all, it is “the greatest privilege of all”, and they have to deserve it.[20]

But Augustus changed his mind on Samos after staying there for the winter of 21/20 and again in 20/19. He had established a relationship with the city’s elites during his stay and must have been impressed with their hospitality.[21] Augustus granted freedom to the city and also dedicated a building to it. In turn Samos dedicated a statue to Augustus. Samos became a colony.[22] This gift of freedom to Samos was an example of the emperor acting unilaterally and autocratically.[23] This shows that developing a relationship with the emperor could change his mind on what privileges he gave to a city or community. It had been many years after the end of the war with Mark Anthony, so there had been time for any tensions between Samos and the emperor to cool off.

This document is relatively useful in telling us about the relationships Augustus had with Aphrodisias and Samos, and specifically the greater importance of the former. It goes briefly into the history of Augustus’s relationship with Aphrodisias and references his wife Livia’s advocacy for Samos. It also explores some of Augustus’ motivations in his decision. However, to properly understand and appreciate the document, one has to do further research on its context and on the events and ideas referenced, such as the war mentioned, the different relationships of the emperor with the Aphrodisians and Samos, and the idea of freedom that the Samians want. Augustus would not need to mention these things as it can be assumed that both he and his audience knew them already.

Bibliography

Augustus. “Augustus refuses freedom to Samos”, 27 BC in The Roman Empire: Augustus to Hadrian, edited by Robert K. Sherk, Cambridge, 1988, 7.

Badian, Ernst. “Notes on Some Documents from Aphrodisias Concerning Octavian.” GRBS 25, (1984): 157-170. https://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/viewFile/5601/5285

Dmitriev, Sviatoslav. “Roman Policy in Greece and Asia Minor.” In The Greek Slogan of Freedom and Early Roman Politics in Greece, 227-282. Oxford University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195375183.003.0007

Edmonson, Jonathan. “The Roman emperor and the local communities of the Roman Empire.” In Il princeps romano: autocrate o magistrato? Fattori giuridici e fattori sociali del potere imperiale da Augusto a Commodo, edited by J.-L. Ferrary and J. Scheid, 127-155. Pavia, Italy : IUSS Press 2015. https://www.academia.edu/4063190/_The_Roman_Emperor_and_the_Local_Communities_of_the_Roman_Empire_?from=cover_page

Jones, Christopher P. “Augustus and Panhellenes on Samos.” Chiron 38, (2008): 107-110. https://publications.dainst.org/journals/chiron/385/4993

Reynolds, Joyce. Aphrodisias and Rome: Documents from the Excavation of the Theatre at Aphrodisias conducted by Professor Kenan T. Erim together with Some Related Texts. Cambridge: 1982.

Thommen, Geraldine. “The Sebasteion at Aphrodisias: An Imperial Cult to Honor Augustus and the Julio-Claudian Emperors.” Chronika 2 (2012): 82-91. https://www.chronikajournal.com/resources/Thommen%202012.pdf

[1] Augustus, “Augustus refuses freedom to Samos”, 27 BC in The Roman Empire: Augustus to Hadrian, ed. Robert K. Sherk (Cambridge, 1988), 7.

[2] Joyce Reynolds, Aphrodisias and Rome: Documents from the Excavation of the Theatre at Aphrodisias conducted by Professor Kenan T. Erim together with Some Related Texts (Cambridge: 1982), 105.

[3] Augustus, “Samos”.

[4] Sviatoslav Dmitriev, “Roman Policy in Greece and Asia Minor.” In The Greek Slogan of Freedom and Early Roman Politics in Greece (Oxford University Press, 2011), 227-29.

[5] Ibid, 233.

[6] Ibid, 253.

[7] Ibid, 270.

[8] Christopher P. Jones, “Augustus and Panhellenes on Samos”, Chiron 38, (2008): 109.

[9] Geraldine Thommen, “The Sebasteion at Aphrodisias: An Imperial Cult to Honor Augustus and the Julio-Claudian Emperors,” Chronika 2 (2012): 83.

[10] Reynolds, Aphrodisias, 105-6.

[11] Thommen, “Sebasteion”, 83.

[12] Ernst Badian, “Notes on Some Documents from Aphrodisias Concerning Octavian,” GRBS 25, (1984): 157-59.

[13] Reynolds, Aphrodisias, 97.

[14] Badian, “Octavian”, 160-61.

[15] Jones, “Panhellenes”, 110.

[16] Thommen, “Sebasteion”, 83-86.

[17] Ibid, 88-89.

[18] Jonathan Edmonson. “The Roman emperor and the local communities of the Roman Empire,” in Il princeps romano: autocrate o magistrato? Fattori giuridici e fattori sociali del potere imperiale da Augusto a Commodo, ed. J.-L. Ferrary and J. Scheid (Pavia: IUSS Press 2014), 144.

[19] Badian, “Octavian”, 168-69.

[20] Augustus, “Samos”, 7.

[21] Edmondson, “Emperor”, 146.

[22] Jones, “Panhellenes”, 109.

[23] Edmondson, “Emperor”, 142.

Leave a comment