Fastia Velsi’s urn was part of a tomb in the Colle Lucioli near Chiusi. The lid of Fastia Velsi’s inscribed travertine urn depicts her wearing a tunic and elaborate jewelry, reclining on two pillows as if in a banquet. The front of the container depicts a youthful figure with wings and fishtail legs. It possibly represents Scylla, a popular image on Hellenistic Etruscan urns.[1] An egg and dart pattern is painted on the moulding above the panel, and each side of the panel has a fluted column. Each side of the urn is decorated with a patera in a sunk panel. On both the front and ends, the portion below the panels is decorated with a double scroll. The back of the urn is unadorned.[2] The retrograde inscription along the lid’s base is translated as “Fastia Velsi, wife of Larza Velu”. Other inscriptions from Chiusi have confirmed the family name Velu.[3] Monsters were represented frequently on these urns as they were central to the Etruscan view of death. They sprang up in Italian art sometime in the late fourth or rarely 3rd century, and their prototype may be the serpent-legged giant with at least one example from the end of the 5th century.[4] The commonality of the Scylla sea monster motif in Etruscan art, along with its role in protecting the dead, may be the reason it was chosen. It is similar to the gorgon’s role as an apotropaic device.[5] This use reflected the growth of simplified decorations on the sides of chests, as opposed to the earlier, more detailed mythological scenes.[6] Fastia’s ornaments and dress are simple, making it different from other effigies which are filled with gaudy jewelry.[7] This may reflect the growing austerity and decline of expensive ornaments and monuments in tombs during the Hellenistic period.[8] Indeed, the depiction of Scylla runs parallel to the simplified decorations on the sides of the chests. But this chest mixes older, more elaborate designs with newer and more austere ones.[9] The decline in elaborate tomb decoration may be because the lower and upper classes were becoming equalized in funerary culture.[10] Mass production of chests by the 2nd century BC further reduced their costs for tombs.[11] Travertine ash chests were the most popular containers by far in the 3rd century BC and showed a peak in the artistic production of funerary containers in Chiusi during this period. Sarcophagi almost totally disappeared at the end of the 3rd century BC. Ash chests of terracotta were introduced at the end of the 3rd century BC, and soon became popular.[12]

Because the Boston urn is the best produced of the tomb’s lot, many of the tomb’s best items were made to accompany it. This indicates that Fastia Velsi was a prominent member of the family and that the Velsi family were elites. All the other burials in the Chiusi tomb are female and the woman were either by blood or marriage all related to men of the Velsi family. The other material in Boston must belong to more than one of the Velsi women.[14] On the related travertine urns at Casa Lucioli, inscriptions reveal names: Thania Titi Cazrtunia Tlesnasa, Fasti Velsi Tutnasa Trepunias, Thana Velsi Tutnasa Trepunias, and Thana Tutnei Vensisa.[15] It is possible that since Fastia was discovered in the same tombs as these other members of her family, she may be portrayed as dining with them in a Velsi extended family gathering in the afterlife, since these banquet motifs are being used for urns in tombs. Starting from the fourth century BC, the depiction of banquets in the urns was aimed at the survival of the nearly material soul of the deceased, instead of reintegration with the living as was done before.[16] Tombs were now less hierarchical and more inclusive because they focused on the collective nature of the family.[17] From the 3rd century BC the chamber tomb became the more dominant tomb type, so the Colle Lucioli tomb is likely to have been of this category.[18] Tombs were now less elaborate because other ways of displaying status had developed, like owning land and euergetism.[19]

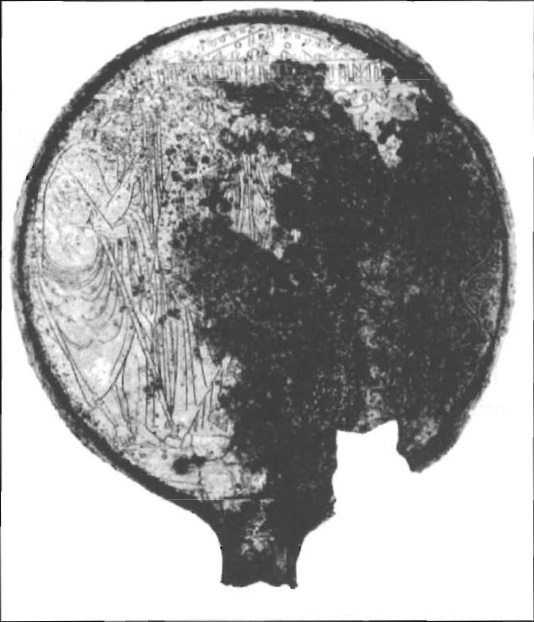

A large tang mirror of bronze in the tomb is theorized to depict Rhadamanthus, one of the judges of the underworld.[20] The mirror’s four figures stand before an elaborate Aeolic façade conversing in pairs. Unfortunately, the mirror has been damaged. A helmet and owl on the right figure indicate Minerva. The female on the left wears plenty of jewelry but is almost nude, and is identified as Turan, the Etruscan Venus. The female wearing a floral diadem is likely Persephone. The male is bearded, leans against a gnarled staff, and wears a himation. The character’s inscription, the most complete one, is likely the Etruscan form of Rhadamanthus, making the mirror the first known appearance of that mythological figure in Etruscan art.[21] The mirror may include Aphrodite because it may have been given to Fastia as a wedding gift meant to bless Fastia’s marriage with Larza Velu. However, scholars are not sure how to interpret the scene. It is likely also meant to accompany and protect her in death.

Other mirrors discovered in the tomb of Fastia Velsi depict Lasas. A Lasa is a mythical, nymph-like Etruscan character. Fastia’s version is female, and there is a less well preserved example showing a male Lasa. [23] Lasa are often portrayed as naked females with wings on late Etruscan mirrors. They can wear jewelry, shoes and a cap. The Lasa in Fastia’s mirror appears to be wearing a Phrygian hat. The running or flying pose is omnipresent in Lasa mirrors. The Lasa mirrors may have acted as sort of “guardian angels”: their tasks included protecting innocents from harm, facilitating or encouraging lovers, and helping brides in their grooming and adornments before marriage. The last two functions show why Lasa are often shown with Turan. By this time the mirrors may have become more readily available in Etruscan society as they were more widespread and less expensive.[24] The protective function the Lasa served is most likely the reason why it was put in the tomb to accompany Fastia to death. The Chiusi tomb overall has eleven associated mirrors.[25]

The Boston tomb also has three forms of silver cosmetic vases. There are two small, amphoriskos-shaped balsamaria. They are well-crafted transport amphoras with pointed bases, which would have been suspended with silver chains. There are also three cylindrical pyxis with domed lids along with three silver strigils. [27] The vases must have all been toilet utilities holding a liquid. The festoons, bucrania, acanthus leaves and feather pattern that appear on most of the silverware were symbols of Hellenistic freedom.[28] Silver strigils are very rare overall.[29]

There is an analogous group from an Etruscan tomb at Bolsena and now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The tomb also had a balsamarium (but with spiral handles instead of a suspension chain), a strigil and a pyxis. All three items have the Etruscan word suthina punched on them. It meant “for the tomb” but this word is not in the Chiusi objects. The use of the word may have been restricted to north central Etruria. All the silver luxury items may have been imported from southern Italian workshops (likely Tarentum).[32] A pair of gilded swags outlines the widest part of the amphoriskos, and gilded acanthus leaves decorate the bottom side. Strigils are often found in the tombs of Etruscan women. They were used to scrape off oil, dirt, and perspiration from the body before bathing. In both Greek and Roman society, strigils were almost entirely used by men, but in Etruscan depictions both sexes use them. They appear on mirrors showing men and women bathing. One mirror shows three of the metal items in the Bolsena tomb group: an amphoriskos, a strigil, and another mirror. The monogram that also appears here identifies the owner as Ramtha Murinas.[33] From these similar silver objects we see further proof that Fastia must have been wealthy, as was Ramtha, to be able to import these elaborate, expensive items.

Bibliography

Daveloose, Alexis. “Funerary Transformations in an Etrusco-Italic Community: Social Display and Austerity in Hellenistic Chiusi.” Papers of the British School at Rome, 85 (2017): 37-69

De Puma, Richard. “A Third-Century B.C.E. Etruscan Tomb Group from Bolsena in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 112 (2008): 429-40.

De Puma, Richard (2013). “Mirrors in Art and Society” from The Etruscan World Routledge, edited by Jean M. Turfa, 1041-1067. London; New York, Routledge, 2016.

De Puma, Richard. “The Etruscan Rhadamanthys?” Etruscan Studies 5, no. 3 (1998): 37-52.

Eldridge, L.G. “A Third Century Etruscan Tomb.” American Journal of Archaeology 22, no. 3 (1918): 251-294.

Huntsman, Theresa (2014). “Hellenistic Etruscan Cremation Urns from Chiusi.” The Metropolitan Museum Journal 19, no. 1 (2014): 141-150.

[1] Richard de Puma, “The Tomb of Fastia Velsi from Chiusi,” Etruscan Studies 11, no. 1 (2008): 135-36.

[2] L.G. Eldridge, “A Third Century Etruscan Tomb,” American Journal of Archaeology 22, 3 (1918): 251-52.

[3] De Puma, “Velsi,” 136-37.

[4] Eldridge, “Tomb,” 252-53.

[5] Theresa Huntsman, “Hellenistic Etruscan Cremation Urns from Chiusi,” The Metropolitan Museum Journal 19, 1 (2014): 145.

[6] Alexis Daveloose, “Funerary Transformations in an Etrusco-Italic Community: Social Display and Austerity in Hellenistic Chiusi,” Papers of the British School at Rome 85 (2008): 43.

[7] Eldridge, “Tomb,” 253-54.

[8] Daveloose, “Transformations,” 37.

[9] Ibid, 58.

[10] Ibid, 46.

[11] Ibid, 44.

[12] Ibid, 40-42.

[13] For this photo of Fastia Velsi’s urn from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, see “bensoiza: The Casual Looting of Etruscan Tombs,” bensoiza, 2013, http://benedante.blogspot.com/2013/07/the-casual-looting-of-etruscan-tombs.html.

[14] De Puma, “Velsi,” 145.

[15] Ibid, 148.

[16] Daveloose, “Transformations,” 53.

[17] Ibid, 59.

[18] Ibid, 43.

[19] Ibid, 60-61.

[20] De Puma, “Velsi,” 145.

[21] Richard De Puma, “The Etruscan Rhadamanthys?”, Etruscan Studies 5 3 (1998): 38-42.

[22] For these images of the Rhadamantys tang mirror see Ibid, 39, figs 3 and 4

[23] De Puma, “Velsi,” 144.

[24] Richard De Puma, “Mirrors in Art and Society,” from The Etruscan World Routledge, ed. Jean M. Turfa (London; New York, Routledge), 1052-56.

[25] De Puma, “Mirrors,” 1061.

[26] For this image of a Lasa mirror from Fastia Velsi’s tomb see Ibid, 1054, fig 58.14.

[27] De Puma, “Velsi,” 139.

[28] Eldridge, “Tomb,” 268.

[29] Ibid, 279.

[30] For these images of an amphoriskos and a pyxis, see De Puma, “Velsi”, pg. 139, figs 7 and 8.

[31] For these images of silver strigils, see Eldridge, “Tomb”, 278 fig 14.

[32] De Puma, “Velsi,” 140-41.

[33] Richard De Puma, “A Third-Century B.C.E. Etruscan Tomb Group from Bolsena in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” American Journal of Archaeology 112 (2008): 433-34.

[34] For this image of the silver objects from the Bolsena Tomb, see De Puma, “Velsi,” 140 fig 10.

Leave a comment