In the first half of the 20th century, Latin America was going through a dynamic change. Social movements were taking control of their national destinies, advancing democracy along with economic equality in countries like Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. But the United States, through its coup in Guatemala, initiated the Cold War which saw both the rise of Marxism and right-wing dictatorships, destroying the dual promises of individual democratic freedoms and economic equality.

Nationalist, popular democratic forces in Latin America helped bring about economic change in Latin America. In Mexico, many different social groups united against the dictator Porfirio Diaz, but after his ousting, their interests diverged. They included the cowboys, miners, railroad, and oilfield workers in the north, along with the peasants in the south. The middle-class group eventually won the revolution, and in 1917 drafted a constitution which nationalized minerals and instituted wage and hour laws.[1] Reforms really got underway in the 1930s with Lazaro Cardenas, who redistributed land, expropriated oil companies which refused to fairly pay workers, and even defended the right to strike. All this won him popularity.[2] Argentina was more middle class and urbanized, so reforms were implemented there peacefully. In Argentina, Juan Peron was popular even as secretary of labor in the 1930s, and despite being removed on October 17, 1945, a large worker’s demonstration in downtown Buenos Aires demanded his return. The industrial working class remained the backbone of his movement. He implemented social services and his government took over nearly every industry. His wife Eva Peron helped win the vote for women in 1947 and advocated equal pay for equal work. Even after a severe middle-class downturn and his exile, Peron remained popular in 1957.[3] Brazil’s Getulio Vargas took power in a 1930 coup after a disputed election the year earlier. He was a nationalist who brought many different groups together and created many governmental social programs. This made Vargas popular despite his transformation into a dictator in 1937.[4] He later returned in the 1950s and won votes as a left-leaning populist.[5] In Guatemala between 1944 and 1954 two nationalist presidents were elected. First Juan Jose Arevalo implemented social security along with a new labor code and constitution. He urged better pay for Guatemalan workers. The next president Jacobo Arbenz implemented land reform and expropriated unused land from the United Fruit Company.[6] Workers and peasants across Latin America were finding their voices and mobilizing into an autonomous political force at this point, powerful enough to effect change from their governments. They insisted on a piece of the pie, and their work was paying off. Economic equality was being advanced with government involvement in the economy, but it was largely being done democratically. However, these promises would be shattered by the US.

The US would initiate the turbulent Cold War period in Latin America that broke the link between freedom and economic equality. Arbenz’s policies irked United Fruit, which lobbied the US government. In response, a US proxy force invaded Guatemala from Honduras, and the Guatemalan army joined and removed Arbenz, starting a vicious dictatorship and civil war.[7] This galvanized the region’s Marxists, with Marxist theories already resonating due to the region’s inequality. One such revolutionary, Che Guevara, made common cause with Fidel Castro and his brother Raul. The Cuban Revolutionaries attacked Cuba twice but failed. The survivors fled to the Sierra Maestra mountains where they hid for the next two years. Discontent against the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista grew, and he eventually left Cuba. The revolutionaries took power in 1959 and immediately executed 483 of the dictator’s henchmen. They refused US pleas to ally with them against the Soviets and expropriated lots of US owned property. In response the US embargoed Cuba. The CIA also put together a proxy force to invade at the Bay of Pigs, but it failed. Cuba was now firmly aligned with the Soviets and accepted their missiles. The Cuban Missile Crisis resulted in 1962, but the US agreed to leave Cuba alone in response to the Soviets removing their missiles. Because the revolutionary government was desperate to industrialize, it became a dictatorship, publicly silencing a well-known poet and forcing middle-class people to chop sugarcane. The Cuban government reasoned that its reforming project required discipline and that it was worth it to infringe on individual liberties. The Cuban revolution inspired many Latin Americans.[8] The US had destroyed the chance to achieve economic equality through democratic liberal means in Guatemala. Marxist elements filled the void and responded with their own revolution in Cuba, no longer committed to democratic liberal values. The Cuban revolutionaries were desperate and swore that their country would not become another Guatemala. Across Latin America, nationalism took a Marxist tilt. But the US was poised to respond, and the stage was set for the Cold War in Latin America.

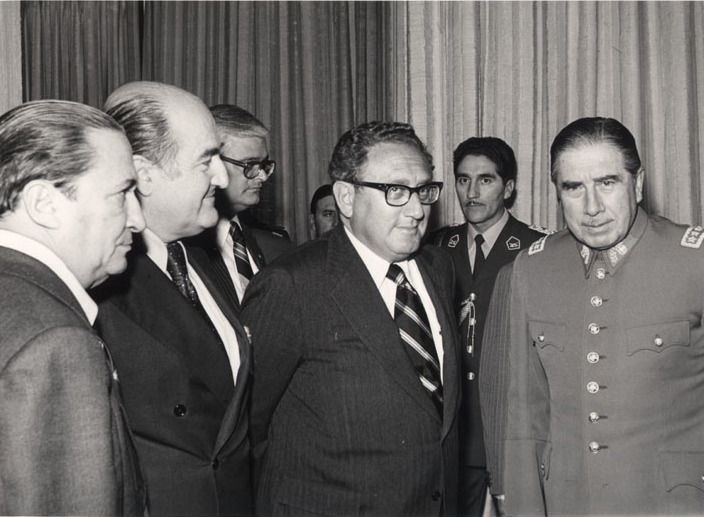

The US aided counter-revolutionary elements in Latin America. At first, John F. Kennedy tried to stop revolution through economic and political reform with the Alliance of Progress. But this proved difficult and was quickly scrapped. Instead, the US helped Latin American militaries as they began to turn on anyone accused of supporting Marxism, employing secret kidnapping, torture, and murder.[9] Brazil’s military took over in 1964. The government ruled in a democratic veneer but gradually chipped away at it. It engendered an “economic miracle” that pacified the middle class but left the poor majority behind. The money was spent on large infrastructural projects. But in the 1970s, the economic growth ended, Brazil borrowed petrodollars and eventually had the world’s largest foreign debt. The military later stepped down.[10] In Argentina, repression was far bloodier and there was no comparable economic growth. Although the military took power in 1966, there were still regular presidents until 1976, when Isabel Peron was overthrown and the military dictatorship went into full force. Most people tried to ignore the dirty war. However, in the late 1970s protesting mothers flooded the Plaza de Mayo, haunting Argentina’s conscience.[11] Argentina’s failed Falklands war in 1982 led to the regime’s fall.[12] In Chile the Marxist Salvador Allende was elected with a narrow plurality in 1970, but his opponents united against him with CIA money and support. On September 11, 1973, Allende was killed by his own military in a coup. Augusto Pinochet took over as a dictator and thousands were tortured and murdered.[13] However, Pinochet also helped the struggling Chilean economy to somewhat stabilize and grow through capitalist policies, earning him some domestic support, and he did step down voluntarily in 1990 after losing a 1988 plebiscite. Mexico did not have militant anti-communism as the PRI used socialist motifs and patronage to keep working and country people satisfied. But the PRI remained a soft dictatorship, and massacred student protestors at Tlatelolco Square in 1968.[14]

Central America remained a Cold War battleground in the 1980s. Landowners still had power in this largely agricultural region. Guatemala’s military leaders repressed rural guerrillas and urban opponents, herding indigenous peasants into rural concentration camps. Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza was overthrown by the Sandinistas in 1979, but his men regrouped in Honduras and with American help rebranded as the Contras. They raided Nicaragua, causing havoc and harming the economy. In El Salvador, the Marxist FMLN revolted against the government and attacked key targets. The military retaliated mercilessly, slaughtering peasants and civilians alike. By the end of the Cold War, exhaustion had brought peace.[15] In all these nations, the military dictatorships had implemented economic liberalism but not political liberalism. Instead, they were repressive, making it impossible to address economic and social problems democratically and peacefully. The regimes’ economies grew inequality and only helped specific people in the upper and middle classes, reversing the social and economic gains made earlier. And the US, despite its self-proclaimed role as the guardian of freedom, was aiding and abetting it all. Ironically, by the end of the Cold War period as Latin America democratized it embraced neoliberalism and turned its back on the earlier nationalist policies for economic equality because neoliberalism appeared to have won.

In the first half of the century, Latin America’s working and lower classes were mobilizing into autonomous sociopolitical forces and advancing individual freedoms and economic equality through their election of nationalist and populist leaders. But the US coup in Guatemala and their support of brutal counterrevolutionary dictatorships took away the promises of both ideals together and reversed the gains that had already been made. While neoliberalism relatively dominates Latin America today, not all people have benefited from it, and left wing and/or socialist leaders have been elected in many countries.

Bibliography

Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America 4th Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

[1] John Charles Chasteen, Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America 4th Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016), 239-40.

[2] Ibid, 256-57

[3] Ibid, 271-73

[4] Ibid, 252-53

[5] Ibid, 265

[6] Ibid, 277-79

[7] Ibid, 279

[8] Ibid, 282-91

[9] Ibid, 298-301

[10] Ibid, 303-06

[11] Ibid, 306-08

[12] Ibid, 314

[13] Ibid, 309-11

[14] Ibid, 313-14

[15] Ibid, 315-322

Leave a comment