In Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, the Squire is one of the characters who gets to tell a tale. His tale is an interlaced romance, a common form in the Middle Ages which was very long. The exotic and fantastical setting of the Squire’s Tale reflects his ambition, talents and imagination, and while he does showcase squirely ideals of service and love in the tale, he is trying to juggle too much and needs to step back.

The Squire sets his tale in a faraway exotic location, “at Sarray in the land of Tartarye” (SqT 9). It was ruled by Cambiuskan (SqT 12). He may be Genghis Khan or his son Batu (The Norton Chaucer 314 n. 4) During the Middle Ages there was a trope of telling Orientalist tales from faraway places in the East. The Squire himself has been “sometimes in chivachye / In Flanders, in Artois, and Picardye” (GP 85-86). Although those locations are not far from England, the Squire appears eager to travel, and his father, the Knight, has gone on many expeditions to places as far as Russia. He is drawing on the experience of his father. It is notable that he has chosen the Mongols and Tartarye as the setting of his story. The Mongols were a famed cavalry civilization, and the Squire himself is a cavalryman, and “wel could he sitte on hors, and faire ride” (GP 94). Cambiuskan’s description has some similarities to the Squire’s. He is described as

Sooth of his word, benigne and honorable,

Of his corage as any centre stable,

Young, fressh, and strong; in armes desirous

As any bacheler of al his hous.

(SqT 21-25)

In the same way, the Squire is described as young, only “twenty yeer of age / […] and wonderly delivere, and of greet strengthe” (Chaucer, GP 82, 84). The Squire in this way is reflecting himself in the Khan, although he is not a direct analogue of him, and the Squire also reflects himself in other characters. The Squire has chosen a banquet to set his story in, which Cambiuskan holds when he “hath twenty winter born his diademe” (SqT 43). He celebrates his birthday feast in “the laste Idus of March after the yeer” (SqT 45-47). The Squire describes the season:

Ful lusty was the wedder and benigne,

For which the foweles again the sonne sheene-

What for the season and the yonge greene-

Full loude songen hir affecciouns

(SqT 51-55)

This appears to be the perfect season for the Squire, who is described “as fresh as is the month of May” (GP 92) While it is not quite the same month, it is still around spring, which is the same season as the Canterbury Tales itself is set in. He is setting up a conventional interlaced romance. The banquet is described as “solempne and so riche / That in this world ne was there noon it liche” (SqT 61-62). It has many “straunge sewes”, “swannes”, and “heronsewes”, and “ther is som mete that is ful daintee holde” (SqT 67-68, 70). There are also minstrels playing before the king delightfully (SqT 77-79). This banquet seems like the perfect environment for the Squire, who himself “coude songes make, and wel endite, / Juste and eek daunce” (Chaucer, SqT 95-96). He is also lively and would enjoy the entertaining and celebratory environment of the banquet, with its different delicacies.

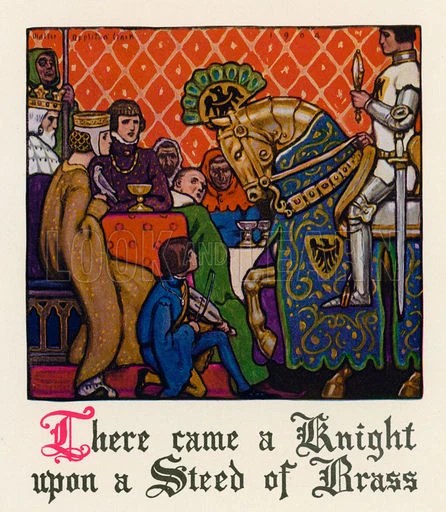

Suddenly, a magical knight on a brass steed rides into the hall (SqT 80-81). The knight Cambiuskan that the king of Arabia and India greets him (SqT 110-12). He gifts the king a “steede of bras” that can ride any distance and fly without getting tired (SqT 115-27). The knight also offers a mirror that “hath swich a might that men may in it see / Whan ther shal fallen any adversitee” (SqT 133-34). He offers the mirror and ring to Canacee, the king’s beautiful daughter (SqT 143-45). The ring allows communication with birds or any creature, and also indicates the herbs that can heal wounds (SqT 149-55). Finally, the sword can cut through any armor even “were it as thikke as is a braunched ook” (SqT 158-59). It can also heal any man if he is hit with its flat side (SqT 162-65). However, all these gadgets remove the challenge from the story. Perhaps the Squire includes these gadgets because they symbolize exaggerations of his skills. That is, the steed of brass represents his skills in riding. He includes the mirror because he is wise, while the ring represents his skills in communication, and the herbs his spring-like personality. Finally, the sword represents his agility and strength in combat. He is better than the average person in these things but is getting carried away in his tale. He is mystifying and enchanting these symbols because he has a creative imagination. However, through all this embellishment he is losing sight of the need for a challenge in the tale. But he does go on to showcase squirely conduct in service and love.

The knight offers gifts to the king and puts himself in his service, performing an analogous role to the Squire. The Squire serves his father well, always carving before him at the table. He is also trying to court Canacee through giving her the mirror and ring, and in a similar way the Squire himself hopes “to stonden in his lady grace” (GP 88). It is the time “dauncen lusty Venus children deere, / For in the Fish hir lady sat ful hye / And looketh on hem with a frendly eye” (SqT 272-74). This is the period to make love, which is why the attendants begin to dance, including the knight:

On the daunce he gooth with Canacee.

Here is the revel and the jolitee

That is nat able a dul man to devise:

He moste han knowe love and his servise

And been a feestlich man as fressh as May,

That sholde you devisen swich array.

(SqT 277-82)

The knight is now engaging in romance with Canacee. The man that knows love and his service is the Squire himself, because the description “as fresh as May” almost correlates with the description that the Squire is given in the General Prologue. The Squire is experienced in love, and he is trying to win his lady’s grace, which motivates his conduct in real life. The knight is also practicing conduct with Canacee by dancing with her.

Later, Canacee wakes up at night after having a vision about her mirror (SqT 367-75). Canacee’s inability to sleep is a direct commonality that she has with the Squire, as “so hote he loved that by nightertale / He slepte namore than dooth a nightingale” (GP 97-98). In the same way, her love for her new gadgets drives her prophetic dream and wakes her up. She remembers her mirror because she is self-reflecting.

She wakes up and goes outside to walk in the woods with her company of six women, and she is “arrayed – after the lusty seson soote / lightly, for to playe and walke on foote” (SqT 389-90) This somewhat echoes the Squire’s gown, which is short but also with long and wide sleeves (GP 93). Canacee’s heart is lightened by

The seson and the morweninge,

And for the foules that she herde singe-

For right anon she wiste what they mente

Right by hir song, and knew al hir entente.

(SqT 397-400)

Canacee is outside walking in spring, which is the season that the Squire is compared to, complete with the singing of the birds, which connect to the Squire since “singing he was, or floiting, al the day” (GP 91). Canacee can also understand the birds due to the ring, and this reflects the musical talent of the Squire.

Canacee encounters a sad peregrine falcon which is hurting itself in its laments, and she understands everything it is saying (SqT 411-37). Moved by pity, she “heeld hir lappe abrood” to catch it (SqT 441). She later asks the cause of the falcon’s sorrow. It responds

That pitee renneth soone in gentil herte,

Feeling his similtude in paines smerte,

Is preved alday, as men may it see

As wel by work as by auctoritee;

For gentil herte kitheth gentilesse

(SqT 479-83)

Here the Squire is showcasing a courtly ideal of having a gentle heart, which is shown both in practice and in the tale. Canacee has pity for the pain of the falcon and is ready to help it. This reflects the Squire’s own personality, as he is always ready to help others. The quote in the first line about a gentle heart is present in several of the previous tales such as the Knight’s (The Norton Chaucer 323 n.1). This shows that the Squire is following their storytelling ideas. It is Canacee’s gentle, lovely and soft heart which brought her outside and by fate led her to the falcon, to discover its tragic story and to save it.

The falcon’s story is a warning on the duality of love. She says that a male falcon dwelt near her, and that he appeared to be gentle with a humble cheer and an appearance of truth (SqT 504-8). She continues

Right as a serpent hit him under floures

Til he may see his time for to bite,

Right so this god of loves ypocrite

Dooth so his cerimonies and obeisaunces,

And keepeth in semblaunt alle his observaunces

That sounen into gentilesse of love;

(SqT 512-17)

The male falcon had concealed his true feelings and personality like a snake, which can move quietly among flowers. The peregrine falcon did not see how sly he was because the falcon had followed all the outward rules and seemed gentle. What the Squire is saying is that what is inside your partner is more important than simply what is outside. She continues, telling Canacee that the male falcon

So longe hadde wopen and complained

And many a yeer his service to me feined,

Til that myn herte – too pitous and too nice,

Al innocent of his crowned malice,

Forfered of his deeth, as thoughte me –

Upon his othes and his suretee,

Graunted him love, on this conticion:

That evermore myn honor and renoun

Were saved, bothe privee and apert

(SqT 523-31)

Notably, both Canacee and the falcon have piteous hearts, but the result is different with the falcon. The Squire teaches that having a piteous heart makes one ready to help, but can also blind them to threats. As a result of being moved by his service and pain, she gave him all her heart and obeyed him in everything, making herself one with him (SqT 541, 568-69). But then he left one day, and the falcon thought he would return (SqT 584-601). She recounts the proverb that “alle thing, repairing to his kinde, / Gladeth”, and that “Men loven of propre kinde newfanglenesse / As briddes doon that men in cages feede” (SqT 608-11). The male falcon had seen a kite fly, and had fallen in love with it, and “hath his trouthe falsed in this wise” (SqT 624-27). The Squire’s lesson here is that it is easy to be bewitched and deceived in love, and that a compassionate heart has both its benefits and problems. It is also a pro-feminine message, as the falcon says that men by their nature love novelty and will leave their spouse. Meanwhile, the female falcon was always faithful to her male falcon, and Canacee is also true to the falcon and is helping it. As in other Canterbury Tales, Chaucer is turning common anti-feminist tropes of medieval literature on their head. The Squire’s story is also aimed at men, telling them that it is not enough to observe the outward courtly rules of love, but that their inner feelings of their spouse and whether they are really devoted to them also matters. The use of birds by the Squire is also fitting since he is quoting Boethius who also used birds as a metaphor for men’s love of novelty (The Norton Chaucer 326 n.2).

The falcon faints and Canacee takes it home and wraps it softly in bandages (SqT 631-638). She then digs up roots from the ground and uses them to heal the falcon, working hard all day and night (SqT 638-42).

And by hir beddes heed she made a mewe

And covered it with veluettes blewe,

In signe of trouthe that is in women seene;

And al without the mewe is painted greene,

In which were painted alle thise false foules,

As been thise tidives, tercelets and oules

And pies, on hem for to crye and chide,

Right for despit were painted hem biside.

(SqT 643-50)

The Squire is further showcasing the ideal of service and aid in his profession in Canacee’s hard work to heal the falcon. But he is showing a female version of it, as gathering herbs and also doctoring would be a female job. The Squire had to do menial, hands-on work. The herbs and their use are only further symbols of the Squire’s spring character and his love of nature. Canacee’s creation of the blue coop surrounded by a pen painted green with treacherous birds is a metaphor for the bird protection by Canacee’s fidelity away from the infidelity and betrayal of the birds outside. The Squire is saying that one must practice fidelity and be a refuge from a world where there is plenty of infidelity. He is also giving hints as to what types of people and what behaviours to watch out for through some of the birds: for example tidifs are known for their loose behaviour, and magpies are notorious for their continual scolding (The Norton Chaucer 327 n. 7-8). So the Squire is giving lessons on service and channeling squirely ideals through both the magical knight and Canacee.

However, the Squire eventually gets carried away in juggling too many plots. He says he will later recount how the falcon repented and regained her love with the help of the ring and the mediation of Cambalus (SqT 652-56). However, he will first talk about adventures and battles:

First wol I telle you of Cambiuskan

That in his time many a citee wan;

And after wol I speke of Algarsif,

How that he wan Theodora to wif-

For whom ful ofte in greet peril he was

Ne hadde he been holpen by the steede of bras;

And after wol I speke of Cambalo,

That fought in listes with the brethren two

For Canacee, er that he mighte hire winne.

(SqT 661-69)

All of these would be common tropes in medieval romances and would also involve knights. Knights would participate in jousts and sometimes in battles, and these would be present in the romances along with the winning of a wife, whether through a quest or battle. These are all aspirations for the Squire, whose father has been to many places and also fought in many battles. He is clearly eager and aiming high.

But the Squire is interrupted by the Franklin, who praises him for his wit and eloquence, “considering thy youthe” (SqT 675). While he is proud and impressed by the Squire’s story, he is also, through referring to his age, implying that he should slow down. The Squire is aiming too high for his age and for his station. He is too young and not yet a knight, so he needs time to hone his craft. Notably, all of the stories he has set forth include knights. Perhaps the setup he has made echoes his future as a knight. He is not yet at that stage which is why Chaucer stops the story here. The Squire has set up a good story and included ideals of squirely service. But he does not need to go any further.

The Squire’s setting of the story at a banquet in a faraway fantastical land reflects his creativity and lively personality, and he represents his ideals of service in the knight and the princess Canacee. He also provides advice and a warning on love through the peregrine falcon’s tragedy. However, in the end the Squire is attempting to cover too much. Due to its incompleteness, the Squire’s Tale has often been confusing to interpret for many people and has also been overlooked. However, it still has valuable things to gauge. It is one of the only tales that Chaucer created on his own. Later writers would eventually take up the Knight’s Tale.

Works Cited

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Canterbury Tales: The General Prologue.” Lawton, David. The Norton Chaucer. Norton, 2019. 77-97.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Canterbury Tales: The Squire’s Tale.” Lawton, David. The Norton Chaucer. Norton, 2019. 314-328.

Lawton, David. The Norton Chaucer. Norton, 2019.

Leave a comment