The novel Emma by Jane Austen explores the life of the eponymous young woman in the village of Highbury. Emma Woodhouse is 21 years old and respected in her community, but also inexperienced in the world. She is close to Mr. George Knightley, a family friend, whose younger brother is married to Emma’s older sister Isabella. This essay will argue that while Emma defines herself through other people’s relationships, Mr. Knightley acts as a mirror who makes Emma more closely examine herself, leading to her realization that she loves him. Mr. Knightley is a more experienced and independent man who values responsibility highly, while Emma is tightly bound to her father and community.

Emma likes to matchmake and believes that she can get others together in relationships. In the beginning of the novel, she has a conversation with Mr. Knightley and her father on this topic. Emma mentions her matchmaking of Mr. Weston with her former governess Miss Anne Taylor. She says that “ever since the day (about four years ago) that Miss Taylor and I met with him in Broadway-lane […] I planned the match from that hour, and when success has blessed me in this instance, dear papa, you cannot think that I shall leave off match-making”. Mr. Knightley disagrees with Emma crediting it to herself, replying that “success supposes endeavour” and that she only made a “lucky guess”. Emma believes that “a lucky guess is never just luck. There is always talent in it”. She says the relationship would have failed if she “had not promoted Mr. Weston’s visits here, and given many little encouragements, and smoothed many little matters”. Mr. Knightley responds that “a straight-forward, open-hearted man, like Weston, and a rational unaffected woman, like Miss Taylor, may be safely left to manage their own concerns” (Austen 11). Emma believes that she has engendered the love between Miss Taylor and Mr. Knightley and is responsible for their marriage. But Mr. Knightley’s argument is that the love was natural, and Emma was merely a passive spectator: they would have married regardless of Emma’s opinion. Emma merely won the game of chance, had a hunch that the two would get along (Wright Lec 1). Mr. Knightley gives more importance to the individual initiative of the man and woman in a relationship than Emma. Emma is very involved in the situations and dealings of others and lacks much of a sense of self. She sees matchmaking as a game.

Later, Emma convinces Harriet Smith to reject a marriage proposal from Mr. Martin. Mr. Knightley is not happy about this. He believes Harriet “has been taught nothing useful, and is too young and too simple to have acquired anything herself” (Austen 48). Emma dissuaded Harriet because of Mr. Martin being a “farmer” who is Harriet’s “inferior as to rank in society”. Mr. Knightley thinks this is absurd because Mr. Martin is “a respectable, intelligent gentleman-farmer” (Austen 49). He says that Mr. Martin “has too much real feeling to address any woman on the hap-hazard of selfish passion” (Austen 50). Mr. Knightley warns Emma that if she encourages Harriet “to be satisfied with nothing less than a man of consequence and large fortune, she may be a parlour-boarder at Mrs. Goddard’s all the rest of her life” (Austen 51). Emma believes that she knows who Harriet should love, and that Harriet needs a man with a high rank. Mr. Knightley’s view is different: he believes that despite Harriet’s high rank, she is inexperienced and naive. She could use someone like Mr. Martin: although he is a farmer and of a lower rank in society, Mr. Martin is independent-minded, self-made, intelligent, and an honest man who gets straight to the point. He is similar to Mr. Knightley, so his relationship with Harriet would be like the one between Emma and Mr. Knightley. Mr. Knightley is considering Mr. Martin on his own merits, while Emma is looking merely at his arbitrary rank in society. Emma is trying too hard to elevate Harriet into an arbitrary rank rather than allowing the natural affection between Mr. Martin and Harriet to play out. By trying to insert her vanity into Harriet, Emma will make Harriet’s relationships fail and harm both herself and Harriet. So Mr. Knightley is taking a hands off approach to love, while Emma is taking an interventionist one.

Mr. Knightley believes that the individual must take responsibility for their situation, while Emma thinks that other factors may keep the individual from doing so. This is seen in their conversation about Frank Churchill. Mr. Knightley argues that Frank “cannot want money” and “cannot want leisure”. He observes that the fact that Frank “was at Weymouth […] proves that he can leave the Churchills”. Emma replies that “we ought to be acquainted with Enscombe, and with Mrs. Churchill’s temper, before we pretend to decide upon what her nephew can do”. But Mr. Knightley is obstinate, countering that “there is one thing, Emma, which a man can always do, if he chuses, and that is, his duty; not by manoeuvring and finessing, but by vigour and resolution. It is Frank Churchill’s duty to pay this attention to his father” (Austen 113). He adds that Frank may “have very good manners, and be very agreeable; but he can have no English delicacy towards the feelings of other people” (Austen 116). Emma thinks Frank’s good conduct and manners are keeping him at Enscombe, as he has to keep his adopted parents happy. Mr. Knightley notes Frank’s freedom to travel. He believes that a real mature man should have the courage to do what is right even based on objections: so Frank should tell his adopted parents nicely that he is going to see his father, and go forth regardless of any objection. Emma and Mr. Knightley’s different views are informed by their respective situations: Mr. Knightley is an independent man who lives alone and manages his own estate, while Emma has to take care of her father (Wright Lec 2). Emma and Mr. Knightley have different interpretations of the word “amiable”: Emma is more concerned with outer manners and sensibility, while Mr. Knightley is more concerned with the truth, real convictions and actions.

Emma’s naivety and frivolity lead her to shamelessly insult Miss Bates, for which she is reprimanded by Mr. Knightley. Emma and Mr. Knightley are together with Miss Bates and several others at Box Hill. Miss Bates volunteers to say “three dull things”, and Emma retorts that she can say “only three at once”. Miss Bates has a “slight blush” in response (Austen 285). Later while they wait for the carriage, Mr. Knightley asks Emma how she could “be so unfeeling to Miss Bates”. Emma replies that “nobody could have helped it. It was not so very bad. I dare say she did not understand me”. But Mr. Knightley reveals that “she felt your full meaning. She has talked of it since. I wish you could have heard her honouring your forbearance, in being able to pay her such attentions, as she was for ever receiving from yourself and your father, when her society must be so irksome”. He adds that Miss Bates “is poor; she has sunk from the comforts she was born to […] her situation should secure your compassion” (Austen 288). As opposed to their earlier conversation about Frank, Mr. Knightley now wants Emma to recognize Miss Bates’ circumstances (Wright Lec 3). While Frank is wealthier, Miss Bates is poorer and is having difficulties in her life. Everyone knows about Miss Bates’ excessive verbosity, so Emma’s jibe is redundant. Emma is looked up to as a model of conduct by everyone else at Highbury. Miss Bates has treated Emma well. Emma comes to realize this, as she had never “felt so agitated, mortified, grieved, at any circumstance in her life” (Austen 289). This is the first time in the novel that Emma has felt regret. Mr. Knightley has told her the truth rather than flattering her like Frank and everyone else (Wright Lec 3). He has challenged Emma to examine herself and who she wants to be to other people. Emma feels that she has failed in her responsibility to be a model for right conduct.

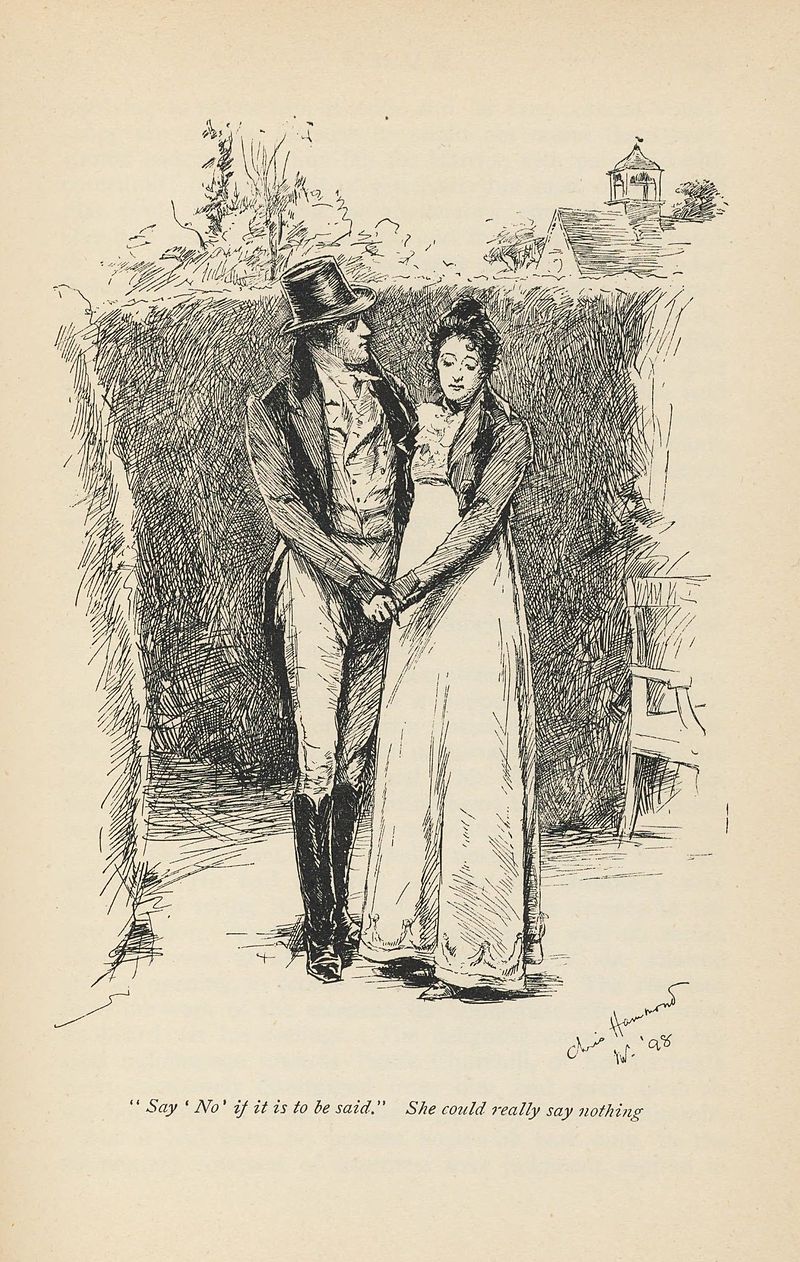

Emma’s love for Mr. Knightley crystallizes when Harriet shares her affection for Mr. Knightley. As a result, Emma “touched”, “admitted”, and “acknowledged the whole truth […] it darted through her, with the speed of an arrow, that Mr. Knightley must marry no one but herself!” (Austen 313). Emma is not happy that she had misread Harriet and her love for Mr. Knightley. She regrets manipulating and leading Harriet on to seek men like Mr. Elton and Frank Churchill, as she may now lose Mr. Knightley to Harriet. The metaphor of the arrow shows Emma that there is no choice for her but to marry Mr. Knightley. Emma has to feel, take in and then accept this truth. The arrow kills Emma’s old self, which influenced other people’s relationships to assert itself. Emma is now realizing that love is something that comes from the individual’s desire, largely independent of any outside interference. Emma now fully appreciates what Mr. Knightley has done for her. Mr. Knightley has tried to make Emma into a responsible individual so that she could have his freedom. Only he has been there to bluntly tell her the truth and to take care of her. This is what a good husband is supposed to do, even if it means upsetting his wife. Later when Emma is talking to Mr. Knightley, she realizes that he loves her, “that Harriet was nothing; that she was everything herself” (Austen 331). Mr. Knightley tells Emma that “nature gave you understanding – Miss Taylor gave you principles. You must have done well. My interference was quite as likely to do harm as good” (Austen 355). Mr. Knightley credits Emma with becoming mature by herself without his help, and actually downgrades his own influence. While Mr. Knightley did have an effect in guiding Emma to individual maturity, it was ultimately Emma who had to take the initiative.

Emma finds enjoyment through influencing the relationships of others, but Mr. Knightley challenges Emma and acts as a mirror who leads her to examine herself more closely, making her realize that she loves him. Emma is commonly considered a bildungsroman exploring Emma’s growth to individual maturity. But it can also be considered as an endorsement of individualism, and the merits of being self-reliant and independent. This type of individualism was a key aspect of the classical liberal ideas that were dominant and growing in Britain during this time period, which emphasized the personal liberty of an individual to do whatever they want without government intervention and extended to the economic level with laissez-faire.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Emma. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1816.

Wright, Daniel. “Emma Lecture 1.” Mississauga: ENG325 The Victorian Novel at the University of Toronto-Mississauga, 10 January 2024. Lecture.

—. “Emma Lecture 2.” Mississauga: ENG325 The Victorian Novel at the University of Toronto-Mississauga, 15 January 2024. Lecture.

—. “Emma Lecture 3.” Mississauga: ENG325 The Victorian Novel at University of Toronto-Mississauga, 17 January 2024. Lecture.

Leave a comment