In the Iliad, Hector is a Trojan prince who leads his people in their war against the Greeks. Book 6 describes his character and reason for fighting. Hector is the Trojans’ pillar, a humble man who accepts his fate but fights so he can earn fame while securing the Trojans’ future. All the Trojans look up to Hector. He knows that Troy will fall, but stands his ground, choosing death for his people over life in escape. Hector is celebrated for this decision.

Hector’s importance for his people is shown from the book’s beginning. He and Aeneas are called upon by Helenus, who describes them as “the mainstays of the Trojans and Lycians”, to rally the Trojans when they are being pushed back to their city.[1] Helenus then tells Hector to ask his mother to give Minerva an offering so she will save the Trojans from Diomedes’ wrath. Hector jumps from his chariot and runs to his men with “the dread cry of battle”.[2] The Greeks fall back, “for they deemed that some one of the immortals had come down from starry heaven to help the Trojans, so strangely had they rallied”.[3] Hector is shown as the rallying point of his men, the only one who can inspire them to continue fighting rather than fall back. Due to his extraordinary battle cry, and the ensuing turn of the tide, the Greeks are scared and demoralized, comparing him to an immortal. Afterwards, Hector runs to the oak tree near the Scaean gates, and the women come to ask him about their “sons, brothers, kinsmen, and husbands”.[4] The oak tree, as a symbol of strength and stability, is a metaphor for Hector’s role as protector of the Trojans. Its location next to the gates shows that Hector is a bulwark against Trojan retreat. Hector tells the women “to set about praying to the gods”.[5] Even as a leader and role model, Hector cannot soothe the Trojan women, because he is only human. Only divine power can save them. But despite such uncertainty, Hector gives them the best answer he can.

Hector follows his duties by taking time from the battle to deliver his message. He arrives at the palace of King Priam, where his mother proposes that he offer wine to Jove before drinking it, but he refuses, “lest you unman me and I forget my strength”.[6] He also dares “not make a drink-offering to Jove with unwashed hands; one who is bespattered with blood and filth may not pray to the son of Saturn”.[7] This shows his humble adherence to tradition: he has earned prestige by defending his city, so he could easily justify taking a drink. But he abstains from alcohol instead, because it will distract him from his duties and weaken him. Hector’s choice reflects the ideas of later Greek philosophical schools like Stoicism which emphasized discipline and abstinence from pleasure. Hector also does not want to taint the sacred with the profane, which is why he is asking the matrons to make the offering to Minerva instead of doing it himself. Rather than celebrating the killing of Greeks, Hector laments the war. He tells his mother Hecuba to have the matrons offer her “largest and fairest robe” to Minerva, and promise to “sacrifice twelve yearling heifers that have never yet felt the goad, in the temple of the goddess if she will take pity on the town”.[8] The Trojans are willing to sacrifice their most prized possessions for divine protection, a common practice in ancient Greece. However, Minerva ignores the priestess Theano’s prayers. This lack of divine favor foreshadows Troy’s destruction, which is fated and cannot be changed. Despite this, Hector and the matrons followed their traditions and respected their gods by giving the offering.

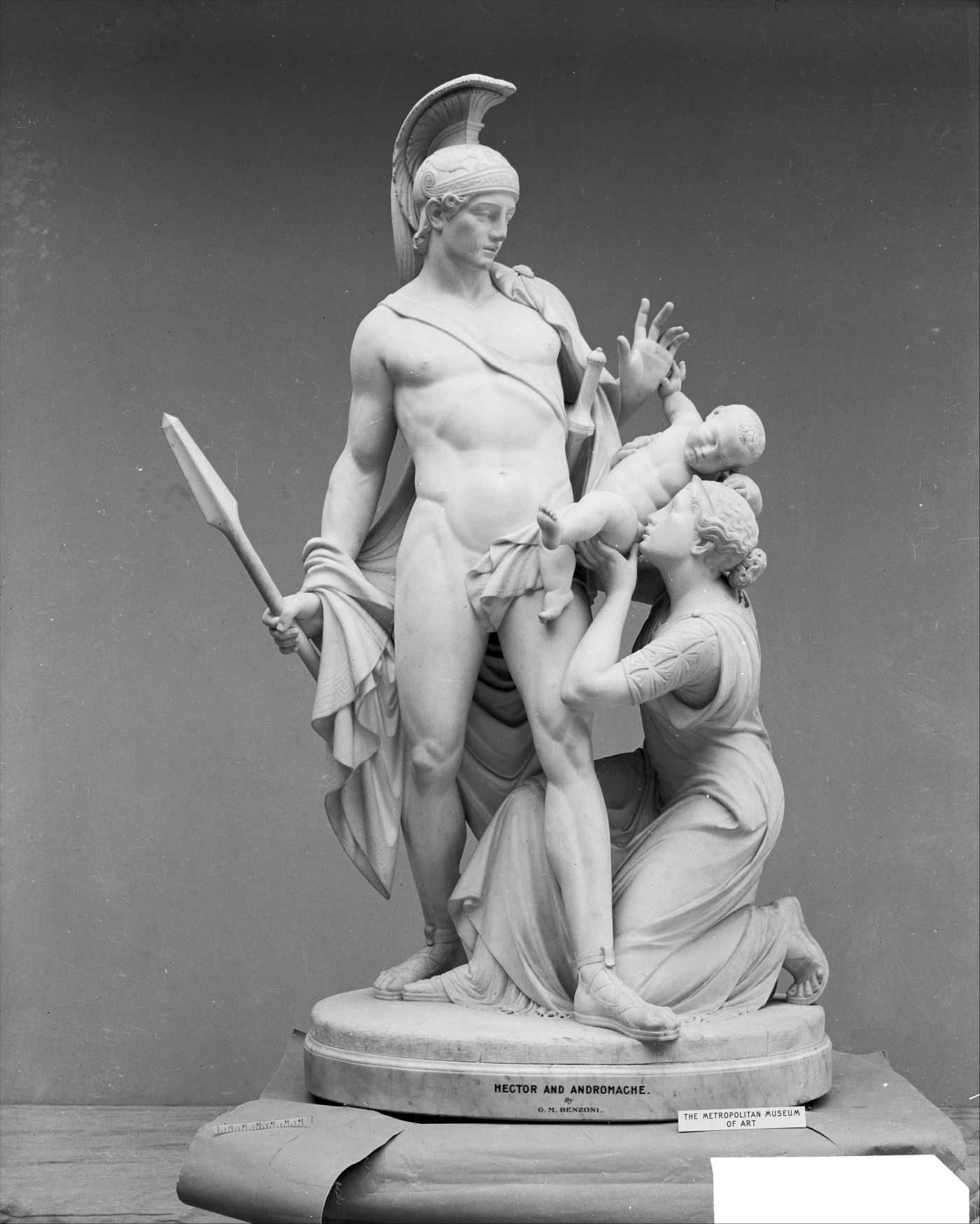

Hector fights to keep his honor and give his people a future. He rebukes his brother Paris for not fighting when “you would yourself chide one whom you saw shirking his part in the combat”[9]. This shows how important it is to Hector for his brother and other Trojans to join him in battle. He has high standards for his men and does not like it when they do not follow them. Paris relents, before Hector goes to see his wife Andromache on the walls of Troy. She pleads with him to stay in the city and move his men to its weakest point, but Hector replies that he cannot avoid “battle like a coward” because “I know nothing save to fight bravely in the forefront of the Trojan host and win renown alike for my father and myself”.[10] Hector reflects the Greek ideal of fighting with one’s men rather than commanding them from afar, followed by kings like Leonidas and Alexander the Great. In contrast, the kings of their Persian opponents generally did not fight in battle. Hector wants to show that he is worthy of being the Trojan champion and win further glory for himself. The Greeks valued great deeds in battle, a trait they shared with other Indo-European peoples like the Vikings. The Iliad praises the deeds of warriors like Hector and Achilles, with the latter going to Troy to win fame even as he knows he will die. Beowulf is another story in the Western tradition exalting the warrior. Death in battle was celebrated, while cowardice was considered worse than it and despised. Hector’s bravery is innate.

Accepting reality also drives Hector’s courage: “well do I know that the day will surely come when mighty Ilius shall be destroyed with Priam and Priam’s people, but I grieve for none of these […] as for yourself […] May I lie dead under the barrow that is heaped over my body ere I hear you cry as they carry you into bondage”.[11] Hector adds that “if a man’s hour is come, be he brave or be he coward, there is no escape for him when he has once been born”.[12] Hector knows that Troy will fall, but prefers dying with his city over outliving it. He could not live with himself if he escaped but his wife was captured and forced into servitude. Hector humbly accepts his fate like the soldier standing guard at Pompeii and refusing to leave his post, even as he knows death is inevitable. But Hector has not lost hope for the Trojans. He prays to Jove and all the gods while holding his son, asking that he may be “chief among the Trojans; let him be not less excellent in strength, and let him rule Ilius with his might. Then may one say of him as he comes from battle, ‘The son is far better than the father’”.[13] Hector has faith that the Trojans’ future can be preserved if his son, wife & other Trojans escape. A pertinent statement is made by Glaucus earlier in the book: “Men come and go as leaves year by year upon the trees. Those of autumn the wind sheds upon the ground, but when spring returns the forest buds forth with fresh vines”[14]. It is currently the Trojan’s autumn, and their city’s destruction is like a painful winter. However, the sacrifices of men like Hector will preserve the Trojan people so they can build something new like spring emerges from winter. This quote also shows the importance of lineage: even if the father dies, the son can carry on the torch if he survives. Even though Astyanax is killed in most Trojan War stories, the later Aeneid by Virgil explores Aeneas’ escape, his travels, and his eventual settlement in Italy. So, despite the death of Hector’s line, his people survived and founded the Roman Empire according to later narratives.

Hector is the role model of the Trojans as he fights even when the odds are stacked against him, sacrificing his life to save his people. Indeed, Hector is killed by Achilles in a duel, and his body is despoiled before the Greek hero, listening to the pleas of his father King Priam, relinquishes it for burial. Some people have suggested that Hector is the true hero of the Iliad, as he defends his people from the Greek invaders, while Achilles is part of the aggressor army. Hector has no choice but to fight, while Achilles does.

[1] Homer, Iliad, 92.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, 92-3.

[4] Ibid, 96.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, 97.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid, 98.

[10] Ibid, 101.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid, 102.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, 93-4.

Leave a comment