Introduction

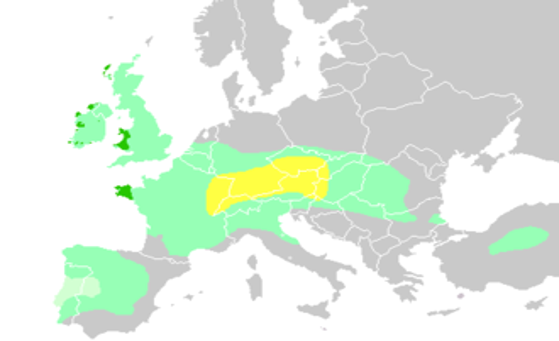

The word “Celt” refers to a people in both modern and ancient times. The Celts today live in the British Isles, along with the Brittany region in the west of France. However, the ancient Celtic peoples were much more widespread, covering areas from Spain, France, the British Isles, Central Europe, Northern Italy, the Balkans and even Turkey. The Celts were divided into many different tribes, however they shared similar languages, cultures and artistic traditions. The Celts are often referred to as the “first masters of Europe” due to being the first people in Europe to cover the whole continent. In this essay, it will be argued that the Celts were an advanced civilization at their peak from the 5th to 1st centuries BC, with advanced metalwork, settlements, and warriors. The Celts had metalworking abilities which were among the best in the world during the Iron Age. The Celts also built advanced hillfort settlements all across Europe called oppida, some of which even reached the status of cities. The oppida were centres of commerce for the Celts’ wide trading network, and some also served as seats for the kings and leaders of Celtic tribes. Finally, the Celts were great warriors who used advanced military technology such as chariots, chainmail armor and their swords to dominate and spread across Europe in their time. Celtic warriors were renowned all across Europe for their ferocity and effectiveness, and they found work as mercenaries even as far as Egypt. This essay will focus on the Celts when they were the masters of Europe, before they were conquered by the Romans.

Celtic Metalwork

Celtic metalworking abilities exceeded those of other great civilizations of their time in the Iron Age. The Celts spread their knowledge of ironworking techniques wherever they migrated in Europe. Gold and bronze were used for luxury items- the Celts wore golden neck bands with sculpted ends, or torcs, along with bracelets and impressive brooches. The natural world was important in Celtic art. Some of the geometric and curvilinear shapes in Celtic art were also influenced by the many other cultures the Celts came in contact with, such as the Greeks, Etruscans and Scythians (Hart-Davis, 2015, p. 125). The La Tene style of Celtic art will be the one mentioned here. Much of the Celtic world, including Gaul, Britain and Central Europe, had deposits of various metals such as iron and tin, which meant that there was plenty of mining going on. This gave them plenty of gold, bronze and other materials with which to create their elaborate metalwork. The richest Celtic Iron Age hoard ever discovered in Europe was in Norfolk, England, containing more than 200 torcs and fragments of them made of gold, silver and bronze dating from the La Tene period in the 5th to 1st centuries BC. Torcs reflected the wealth and status of their owners. The Great Torc, the largest torc found, has eight ropes of gold twisted together forming the neck ring and is more decorated than the other torcs, with flowing curves and a balance between sophisticated decoration and empty space. It dates from the 1st century BC. The metalsmiths who made this torc took inspiration from continental designs, but at the same time added a distinctly British flavor to their craft. The torc also had different metals such as gold, mercury and bronze gilded together in an extremely advanced way (Roberts, 2015). The Gundestrup cauldron, found in a peat bog in Denmark, is the largest surviving piece of silver from the Iron Age period. Although much of its art appears to be Celtic and depicts its mythology, it also has Thracian influences. It is believed to date from the 2nd to 1st centuries BC. It is not known where it originated, though the accepted theory is that the cauldron was commissioned from Thracian silversmiths by the Celtic Scordisci tribe in modern day Serbia (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, n.d.). The Agris parade helmet in France, a masterpiece of Celtic art, is made in gold leaf over bronze and shows some Mediterranean influences. The Celts also began to produce coins from the 3rd century BC, both imitating Roman and Greek types while applying their own tastes to the objects such as horses.

In Britain, luxury metal products were rare before the 2nd century BC due to a lack of surplus wealth and desire for display. However, there were still some specialist metalworkers, which is evident in the cauldrons found in the west, possibly Ireland, along with harness-fittings and cart-trappings, all from the Bronze Age. The swords and daggers found in the Thames point to a tradition of inventive craftsmanship. Production began in the late second or early first millennium BC, with the creation of local bronze daggers copied from the continent. Later in the eight century the Hallstatt style was adopted in Britain, and new Continental trends in the sixth and fifth centuries led to the creation of a British dagger series which persisted until the end of the third century. After that swords, based on the continental La Tene forms, became common again (Cunliffe, 2005, p. 471). The dagger sheaths show high degrees of skill although they were not as elaborate as the ones in the continent. Some of the most elegant pieces found in Britain include the shield boss found in the River Trent near Ratcliffe-on-Soar, inspired by the continental ‘Waldalgesheim style’ and has running scrolls of linked fleshy triangles (Cunliffe, 2005, p. 473). By the 2nd century BC British craftsmen developed highly accomplished works of art. An example is a bronze shield from the River Witham in Lincolnshire. The Waterloo Bridge helmet and the Battersea shield demonstrate that parade gear was widely produced through the first centuries BC and AD. During this time developed a series of centres producing such artefacts, sometimes enlivened with decorative motifs, which a large percentage of the population would have aspirations to (Cunliffe, 2005, p. 483). Many other works of art were produced by craftsmen such as brooches, mirrors, tankards, bowls and a wide range of harness trappings. The craftsmen were skilled in the art of bronzeworking and enamelling, practicing and developing elements of the British insular art style (Cunliffe, 2005, p. 484). So, the Celts were outstanding metalworkers.

Celtic Settlements & Trade

The Celts built settlements all across Europe, some of which even reached the status of cities. Celtic settlements were centres of commerce, and some even served as the seats of power for Celtic leaders. The earliest ones were developed between the sixth and fifth centuries BC as a consequence of demographic growth, centralized power and the establishment of a hierarchy (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 1). The Greek historian Herodotus mentioned a city of the Keltoi called Pyrene, which is believed to be the ancient Celtic settlement of the Heuneberg near the river Danube in southern Germany, dating from 600 BC. It was a huge walled settlement, and the construction of the walls, which were painted white, reveals Greek influence. The site also shows evidence of trade with the Greeks, including Greek ceramics and wine amphoras in exchange for textiles and manufactured goods from the Heuneberg. While Classical Greece was a rich consumer society, the Celtic world was rich in raw materials (Rudgely, 2006). Farming, along with the mining of iron, created the wealth that the Celts used to import luxury goods from Greece and the rest of the Mediterranean world. The grave of an ancient Celtic prince in Hochdorf, Germany, was full of elaborate golden objects such as a dagger and torc around his neck. The prince was laid out in a Greek bronze couch and had a Greek style wine cauldron. He also had a four-wheeled decorated wagon laid with feasting and drinking equipment. This shows that the Celtic prince was a cultured diplomat with international contacts and was in a position of great power as the chief of Hochdorf (Rudgely, 2006). Other sites from this period include Mont Lassois and Bourges in France (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 9). However, many of them would later be abandoned around the 5th centuries BC due to climate change along with social turmoil and warfare. This is not so exceptional, and it happened to many early cities in the world (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 10). Not all regions suffered this though, as Celtic settlements in Britain and Iberia became larger rather than smaller (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 16). In the second half of the 5th and the first half of the 4th century BC, large hilltop centres would pop up in the Middle Rhine-Moselle region, but most were only temporary sites with small temporary populations, and were not as large as the previous settlements (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 11).

From 150 BC to the Roman Conquests of Gaul and Britain, large fortified settlements called oppida popped up all over Celtic Europe from Britain and France to Hungary. They appear to have been founded by a process of synoecism directed by powerful aristocratic families in areas like Gaul, enabling a more hierarchal and centralizing ideology to be articulated (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 24). They served as central places for tribal and sub-tribal polities, periodically visited by the majority rural population (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 28). A number of oppida can be identified by name: for example, Bourges in France was besieged and captured by Julius Caesar, while Bibracte, also in France was the capital of the Aedui tribe and the location of the pan-tribal council where Vercingetorix was made chief of the Gallic confederation against Caesar, while Stanwick was the capital of Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes tribe at the time of the Roman invasion of Britain (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 20). The oppida, though diverse, were characterized by their impressive fortification systems, combining defensive, ostentatious, and symbolic functions. Walls and gates were important for protection. Burials, animal bones and deposits of objects such as coins or weapons close to fortifications shows ritual practices, suggesting that walls, ditches and gates possessed legal, political and sacred significances (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 21). The oppida were main centres of trade, production and distribution, with specialisation and mass production of coins, wheel-turned pottery, iron-smithing and glass production. There were urban sites in Europe other than the oppida though: some were open agglomerations located on lowlands, such as Berching-Pollanten in Germany and Nemcice in the Czech Republic, which also show signs of trade and imports such as Mediterranean amphorae. (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 23). The oppida had empty spaces within their walls. Some were used for farming, while others were used as plazas for religious and political gatherings along with fairs and celebrations (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, pp. 25-26). Many oppida had their origins in spaces for religious gatherings, including Manching, Bibracte, Heidetrank, and Ulaca (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, pp. 28-29). The oppida did not immediately end in Celtic European lands when they were conquered by the Romans, in fact many were converted to Roman cities and continue to be inhabited today such as Bourges and Besancon in France (Fernandez-Gotz, 2017, p. 31). So, the Celts were able to produce settlements which can be classified as urban.

Barbarians?

Some people dismiss the Celts as barbarians due to their lack of writing and the lack of much surviving architecture from their period, while the other ancient civilizations such as Egypt, Greece and Rome had these things and their buildings are still around for people to admire. However, this is highly misleading. There are many reasons why Celtic architecture does not survive to the present day. During the Bronze and Iron Ages, Northern and Western Europe were abundant in wood and has extensive forests. Wood was everywhere and was used for nearly everything. Working with wood became easier than ever with the smithing of bronze tools. Although some stone and natural features were used for building hillforts, the main building material of the Celts was wood. This was due to its plentiful supply and the weather too: in the cold winters of Northern and Western Europe, stone would not have been a good insulator. Wooden structures could be built faster and were better insulated. Obviously, after thousands of years wooden structures rot and burn, leaving little left but holes dug into the ground. Archeologists try to reconstruct the appearances of the Celtic houses from the holes, but what they come up with ends up being ridiculous and far beneath the technical skills of the Celts. They often assume the Celts had no knowledge of joinery and could not even build a wall without huge gaps between the boards. They often depict all Celts as living under primitive huts, at the same time as they were producing elaborate golden works and weapons adopted by Greece and Rome. If the Celts were capable of such talents with metal, they would have definitely been able to create good wooden structures. The average Celt was likely living in a basic home, but that was also the case for other ancient civilizations like Greece and Rome. The only buildings remaining from those great civilizations would have been the most elite and expensively constructed ones which were often built using large slave armies. Celtic rulers definitely had their own grand palaces, built using the fanciest woodwork with carvings in every beam (Fulsom, 2017). Celts also did know how to write, as they had been interacting with the advanced civilizations of the Mediterranean for centuries. Some Celtic peoples had writing scripts such as the Celtiberian in Spain and the Lepontic in what is now southern Switzerland and northern Italy. The Gauls also used three different scripts for their language: Etruscan, Greek and later Latin (MNAMON, 2017). However, usually Celts did not commit their history to writing. This was due to Celtic spiritual beliefs that it was better to orally transmit their stories and histories. Indeed, that is no strange idea: Socrates himself never wrote down a word. It was believed that writing everything down weakened the mind and culture, allowing people to forget things without care (Fulsom, 2017). Therefore, the fact that most Celtic structures do not survive today absolutely does not mean they were primitive barbarians.

Celtic Warriors

The Celts were also great warriors who used advanced military technology such as chariots and chainmail to dominate Europe in their day. The Celts were feared and respected by the Greeks and Romans due to their military prowess and strong warrior ways. They often stood a head taller than their Mediterranean opponents. Celtic warriors developed different styles of warfare in every region that they inhabited. For example, in Spain they became master swordsmen, while in southern Gaul they had impressive armor with long swords and in Britain they mastered the use of chariots adapted to rough terrain (Ancient Military.com, 2012). Another reason the Romans feared the Celts was because the latter had invaded the Italian under their chieftain Brennus and sacked the city of Rome in 390 BC. They only left the city after the Romans had given them a payment of gold. It took the Roman military 500 years to best their Celtic rivals. The Celts also invaded Greece and looted Delphi in 279 BC before heading over to modern-day Turkey and founding the kingdom of Galatia in its central part. During the Punic Wars, Celts served as mercenaries in the Carthaginian army, and Hannibal had a personal guard of Gestae. However, Celtic tribes usually fought each other for territory, despite the culture that they shared. The Celts used many weapons in battle. Ranged weapons included javelins, harpoons, bows and slings. Spears, two-handed hammers, axes and swords served as close-range weapons, although the main weapon for most warriors would be a spear. Celtic champions would have had better crafted weapons than young warriors. The sword used by Celtic tribes in Spain, which was short, double sided- and ideal for stabbing, became the model for the Roman gladius (Ancient Military.com, 2012). For armor, the Celts used breast plates and chainmail, which was a Celtic invention. Leather armor, light bronze breastplates, scale armor and chainshirts were later used. Ceanlann armor was a type of scale armor developed by the Celts. It was a layer of metal scales sewn onto linen, which in turn was sowed onto chain armor, creating a very effective multi-layered armor (Ancient Military.com, 2012).

Helmets were also important, and examples include the Montefortino and the Coolus helmets, which the Romans imitated for their legionnaires. The Belgae had a type of helmet which was cone-like with a long, square and straight plate to protect the neck. Some Celtic helmets had horns attached to them in order to give the warriors a fierce look. Some Celtic tribes also painted themselves with blue plant dyes in order to appear intimidating to their enemies. The Celts used round shields for light infantrymen and cavalry and long shields for heavy infantrymen. The Roman shield called the scutum was influenced by Celtic shields. However, it was mostly nobles who wore armor and helmets during the early La Tene period (Ancient Military.com, 2012). The Celts were skilled horsemen and frequently employed chariots in battle which were encountered by Julius Caesar during his invasion of Gaul. The chariots were light and pulled by two horses, and had open fronts and backs with double hoops at the sides. They contained two men and were used to attack enemy cavalry. First the charioteers threw javelins, before one man dismounted to fight on foot while the driver rode to a safe distance, ready to retreat if necessary (Cartwright, 2016). The chariot was central to Celtic warfare and was also used a lot in Britain: when Caesar landed in Britain in 55 BC, he encountered chariots in the beach. In 60 AD, Boudicca also used chariots in her rebellion against the Romans in Britain, and Calgacus used them 25 years later to stop the Roman advance into Scotland (Cunliffe, 2005, p. 494). The average Celtic warrior was a light infantryman, fighting unarmored in a battle line formation. Before a battle, scores of Celtic warriors blew on trumpets called carnyxes in order to intimidate the enemy. Polybus, in his description of the Battle of Telamon fought in Italy in 225 BC, gave a frightening description of the battle, mentioning how terrified the Romans were from the Celtic hornblowers and trumpets along with their war cries (Cunliffe, 2005, p. 493). The mass charge was the Celts’ most effective tactic, described by the Romans as “the Furor Celtica”, and it could quickly overpower an enemy. The Celts also fought defensively, and could form deadly shield walls around their chariots. In Galatia, the Celts fought with a phalanx formation, which they possibly picked up from the Greeks. The Celts also occasionally used guerilla tactics and nearly overpowered Caesar during the Gallic Wars with them (Ancient Military.com, 2012). Therefore, the Celts were among the best warriors in the ancient world.

Conclusion

The Celts were a technologically advanced civilization at their peak. They had excellent metalworking abilities exceeding those of other civilizations, and the art in their metalwork was stunning. The Celts had large hillfort settlements, some of which even reached urban status. They were centres of trade, and some even served as seats for the high kings of Celtic tribes. The Celts also had a wide trading network. Finally, the Celts were excellent warriors who used their superior weapons and military technology to dominate Europe in their time. They were renowned all across the ancient world for their military prowess, and they served as mercenaries as far as Egypt. In closing, schools and academic institutions should put more emphasis on teaching about the Celts. Popular culture has a huge fetish for the classical civilizations of Greece, Rome and Egypt, and classical history departments at school devote a lot of resources and energy on studying those ancient civilizations. However, not as many resources or appreciation is put into researching and teaching about the Celts and their great civilization, despite the fact that they were extremely advanced with a deep culture and history, and are among the ancestors of many Europeans who are not of Mediterranean descent, including those from the British Isles and France. As a result, many people of Northwestern or Northern European descent identify their ancient civilizational roots with Greece and Rome and lack appreciation and/or knowledge of their own native civilizations. If more is learned about the ancient Celts, then there will be further appreciation of them in our culture, and many important lessons can be learned from them.

References

Ancient Military.com. (2012). Celtic Warriors. Retrieved from Ancient Military.com: http://www.ancientmilitary.com/celtic-warriors.htm

Cartwright, M. (2016, July 22). Celts. Retrieved from Ancient History Encyclopedia: https://www.ancient.eu/celt/

Cunliffe, B. W. (2005). Iron Age Communities in Britain : An Account of England, Scotland and Wales From the Seventh Century BC Until the Roman Conquest. London: Routledge.

Fernandez-Gotz, M. (2017). Urbanization in Iron Age Europe: Trajectories, Patterns and Social Dynamics. Journal of Archaeological Research.

Fulsom, K. A. (2017, April 6). Why No Ancient Celtic or Germanic Architectural Wonders? Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KM5M1YlKQjM&t=83s

Hart-Davis, A. (2015). History: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Present Day. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

MNAMON. (2017). Celtic, writing systems. Retrieved from MNAMON: Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean: http://mnamon.sns.it/index.php?page=Scrittura&id=58&lang=en#presentazione

Roberts, A. (2015, October 4). The Celts: not quite the barbarians history would have us believe. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/oct/04/celts-great-torque-snettisham-hoard-british-museum-alice-roberts#comments

Rudgely, R. (2006). The Celts. Retrieved from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ij7RTMbFDwY&index=1&list=FLP47pRibTm6doypp-7VQI9A

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (n.d.). Gundestrup Cauldron. Retrieved from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: http://www.unc.edu/celtic/catalogue/Gundestrup/kauldron.html

Leave a comment