The rulers of 17th century Europe had trouble colonizing Canada. A freezing, harsh, rugged and unexplored land, Canada was not too likeable for England, France and Spain. But those who did go to Canada found a flourishing system of trade and recognized that it could be an economic boon.

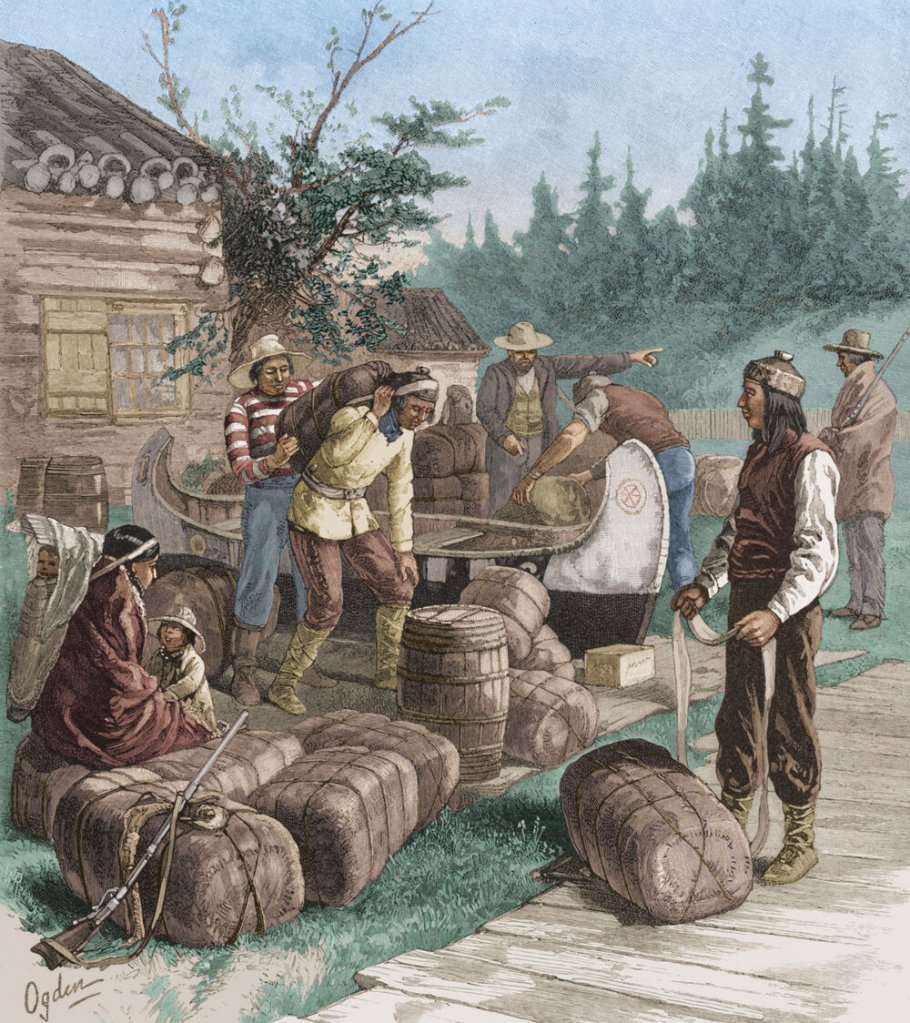

The fur trade: The Indian tribes that the British and French encountered were inquisitive and mostly friendly. They became attracted to European metalware, which was far more advanced than their rudimentary stone and wooden tools. Due to this the Indian relationship with the Europeans turned to one of dependency which would have an unprecedented change on their lives.

At first the Indians did not have much to trade in return for the precious knives and axes, and the Europeans complained that the handcrafted canoes and shoes they received were comparatively useless. But by the late 1600s the Indians had started to trade luxury furs with the Europeans. When Europe’s hatmakers received Canadian beaver pelts, they created beaver hats and marketed them as the warmest and most durable in the world, and thus created a giant demand for furs in the new colony that would last for nearly 200 years. Although the Indians never understood the “white man’s” obsession with the beaver, they turned into the principal suppliers of pelts to the fur merchants and in return were given many European manufactured products. The 17th century writer Marc Lescabot mentioned how the Indians became astonished by the beaver since it had strangely obtained for them kettles, axes, knives and provided them with food and drink without them needing to do back-breaking work on the land. By the early 1700s the fur trade in Canada was very profitable and a struggle for the dominance of the fur market in North America had begun.

Father of Canada: The French explorer Samuel de Champlain expanded the fur trade in many ways. A visionary with a love for exploration, Champlain is considered the “Father of Canada” and is exalted for wishing to found Canada upon the values of justice and compassion.

In the name of the French monarchy, Champlain founded the first French colony in America in Acadia (Nova Scotia) in 1604. Acadia would later be mythologized as a pleasant French settlement where peace and prosperity prevailed and many folktales and poems were inspired by its small villages in the beautiful Maritimes. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem Evangeline memorialized Champlain’s Acadian village of Grand Pre. The tale tells of a town’s idealistic existence being destroyed by the harsh British rulers and two lovers being separated. Longfellow wrote of Acadia and the Acadians:

Thus dwelt together in love

these simple Acadian farmers…

Neither lock had they to their doors,

nor bars to their windows

But their dwellings were as open as

day and the hearts of the owners;

There the richest was poor and the poorest lived in abundance.

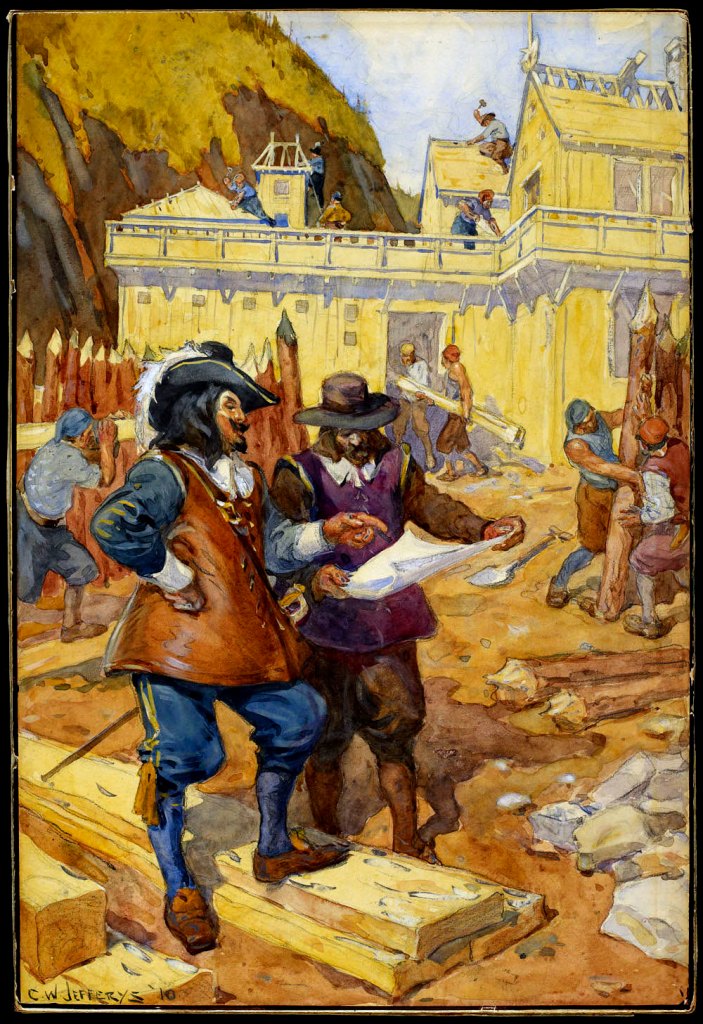

Champlain moved on from Acadia into Canada’s interior and on July 3, 1608, he founded Quebec on the area of an old Indian village called Stadacona. Although this was a historically significant even for Canada, Champlain though the founding of Quebec was rather unextraordinary, and he revealed in his journal that he selected the location not so much for its historical significance, but rather for convenience: “When I arrived there [Quebec] on July 3, I looked about for a suitable place for our buildings, but I could not find any more convenient or better situated than the point of Quebec, so called by the savages, which is filled with nuts and trees…near this is a pleasant river, where formerly Jacques Cartier passed this winter.” (the “pleasant river” is the Gulf of St Lawrence, which turned into a crucial route for the export of furs to Europe).

The Indians and Les Coureurs de Bois: One year after Champlain founded Quebec, a band of Indians emerged from the northwest to trade their pelts with the French. When they got there, the Frenchmen were amazed at how their half-shaven heads looked and their tussocks of hair that grew orthogonally to their scalp. Since this reminded them of the bristles on the back of a furious boar, the French named them Hurons. Thus started a lengthy and tragic relationship.

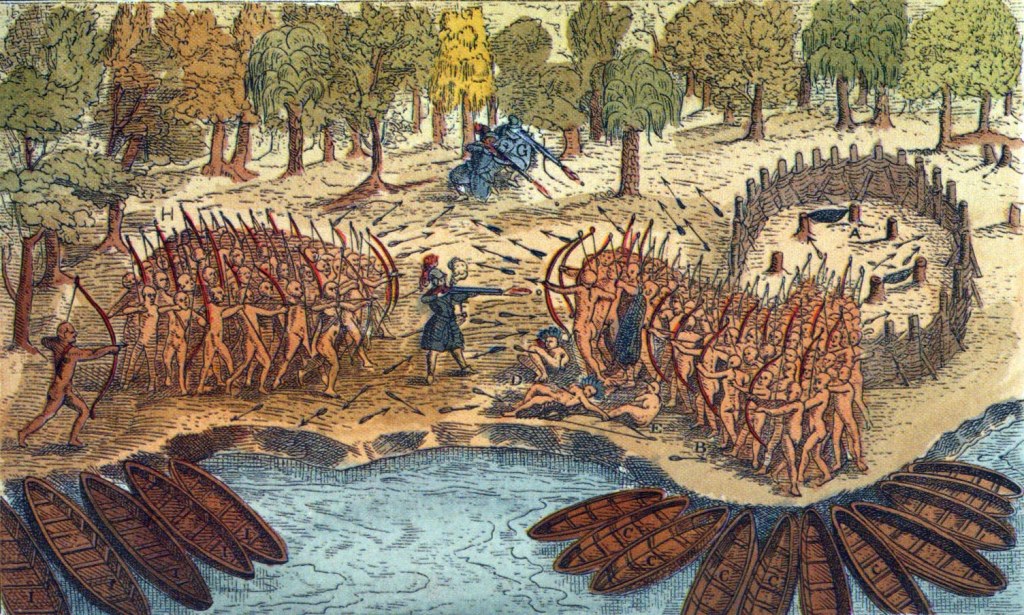

One of Champlain’s principal goals in Canada was to control the booming fur trade and manage the Indians more stringently. Champlain did not see that the fur trade aggravated enmities between the Indian tribes that already existed. The Huron and the Iroquois Confederation had always had resentments of a very ritualistic nature.

The fur trade added a mercenary factor to these hostilities. Champlain’s alliance with the Huron quickly made him the enemy of the Iroquois (which the British would later take advantage of).

The war between the Iroquois and the French began with Champlain’s famed mission to Ticonderoga with 60 Huron warriors and three armed Frenchmen. Although the clash started without gunfire, Champlain’s firearms killed 300 Iroquois. This incident engendered a strong and long hatred for the French among the Iroquois, and they began to fiercely raid French trading posts.

While Champlain structured his colonies and defended against enemy Iroquois, other colonists, primarily men from France, arrived. Called the coureurs de bois, or the woodsmen, these men had humble jobs back at home, and they saw New France as an escape from a life of toil – many had traded prison sentences for emigration papers. The coureurs de bois turned out to be central to Canada’s trading structure.

They were Canada’s early entrepreneurs, brave men trapping animals for their livelihoods. This required a perilous existence in the bush and defense against hostile Indians. In French Canadian folklore, the coureurs were depicted as fearless, robustious and venturesome fellows, and they became the employees of big European companies looking to dominate trade in the New World.

By the 1750s, Canada had become an economic boon for the French, and Britain began to feel more serious about the colony it had ignored for nearly half a decade.

The Settlers: When Samuel de Champlain and other adventurers reached Canada, their inventive plans for the colonization of their settlements were reflections of the European monarch’ lofty visions. They saw Canada as simply an addition to the growing empires of England and France

Canada was a valuable holding in the game of the dominance that the superpowers of the 17th and 18th century relentlessly fought against each other. But for others who ventured to Canada, the farmers and fishermen, the women and children, the missionaries and even the foolhardy coureurs de bois – Canada was not merely a property, but a real place, vacant and huge. And life could be very difficult sometimes.

The Priests: Samuel de Champlain’s two goals in Canada were to strongly regulate the fur trade and to convert the native peoples to Christianity so that the continent could truly be made for “the glory and praise of God and France. The years 1632 to 1652 are usually sited as the “golden years” for Canada’s missions. But this phrase is kind of deceptive since, while it refers to the strong religious activity that occurred in Canada during this time, it hides the low rates of successful conversions.

Four Recollets were the first missionaries arriving in Canada under Champlain. They were strict Franciscans who passionately headed into the wilderness to find the “heathen savages”. The Recollets, thinking that their strict vows of poverty made them prepared for their difficult lives in the wilderness, patiently worked hard on saving Indian souls – but did not have much success. Soon after, the Jesuits were called to serve in the Canadian missions, and in 1625 Fathers de Brebeuf and de Noue departed France to start converting the Iroquois and Huron.

The Jesuits, along with the French and most Europeans, were confused by the Indian lifestyle. Living collectively, without hierarchical structures and forms of authority, blatantly polytheistic and with contrasting notions of diet and sanitation, the Indians appeared to be “barbaric” and “uncivilized” to the French.

Champlain displayed such a view with his writings on the Indians in 1609: “There is an evil tendency among them to be revengeful, and to be great liars, and one cannot fully rely upon them, except with caution and when one is armed… [they] do not know what it is to worship God and pray to Him, but live like beasts, but I think they would soon be converted to Christianity if some people would settle among them and cultivate their souls”.

The Christianity that the Indians were converted to was French Catholicism. Due to this, along with monotheism, the Indians were introduced to many European ways, such as class specialization, the corporal disciplining of wives and children, a privately structured family, and the danger of eternal damnation for unrepentant sinners.

The Jesuits were often rejected by the Indian societies and several of the missionaries, named “black robes” by the Iroquois, came to symbolize evil and bad luck. Although they were ethnocentric, some Jesuit missionaries displayed strong bravery and fortitude. Many were brutally killed and became Canada’s first martyrs. This was the fate of the renowned Father Jean de Brebeuf, a Jesuit who worked with the horticultural Huron for several years.

Christophe Regnault, a contemporary of Brebeuf, wrote of his martyrdom on March 16, 1649 in Jesuit Relations: “The Iroquois came… took our village and seized father Brebeuf and his companion; and set fire to all the huts. They proceeded to vent their rage on these two fathers, for they took them both and stripped them naked and fastened the, each to a post. They tied both their hands and feet together. They beat them with a shower of blows from cudgels… there being no part of their body which did not endure this torment.”

The unlucky priests suffered other brutal tortures, such as the pouring of boiling water over their heads in mockery of baptism, and the placing of hot collars of axe heads around their necks. According to the record, even as he suffered, Brebeuf did not stop preaching to the Indians until they chopped off his tongue and lips. After he had died slowly and agonizingly, his strength so amazed the Indians that they chopped off his heart and ate it, thinking that they would gain his bravery by doing so.

Canada’s first Francophones: In Canada’s early history, two kinds of pioneers headed to the new world. The coureur de bois was an adventuresome woodsmen who embarked into the forest areas he called the pays d’en haut (high country) and both fur trapped and traded for a living.

On the other hand, the habitant, or settler, went to the fertile banks of the St Lawrence River and farmed the land. From the start the two ways of life diverged, and ended up so radically different that resentment grew. The habitant believed the fur traders were as perfidious and vindictive as the Iroquois, while the coureur de bois blamed the colonist for scaring away all their game and forcing them to venture deeper into the wilderness.

Even though the coureurs de bois are often thought to be the more vigorous of the two, the habitant also faced many difficulties. Grueling, toilsome work was needed to clear the tree-filled lands of the St Lawrence banks, crops usually started slowly and harsh weather could immediately wreck a year’s food.

Women needed to work for many hours to complete domestic tasks and then moved on to the fields to work there. In the beginning the very terrain appeared hostile and strange to the habitant; wild animals and enemy Indians were unceasing troubles. The habitant especially feared that he would have a son escape the farm (where his help was crucial) to join the coureurs de bois’ romantic life.

The first homes in New France were rudimentary wooden huts made of hard logs; in the winter, water needed to be obtained from a hole in the ice. Even more insufferable was the ubiquitous cold, which was so unpleasant and irritable that one felt like the marrow in their bones froze. The poet Standish O’Grady had this to say about the cold in early Canada:

Thou barren waste, unprofitable strand

Where hemlocks brood on unproductive land,

Whose frozen air on one bleak winter’s night

Can metamorphose dark brown hares into white.

But there were also payoffs to be earned. Before long the wooden huts were upgraded to stone houses with steep roofs and big fireplaces providing heat. As the forests were cleared, and as farmers flourished on their plots of land, life improved and eventually the living standards of New France’s inhabitants became higher than those of their fellow Europeans.

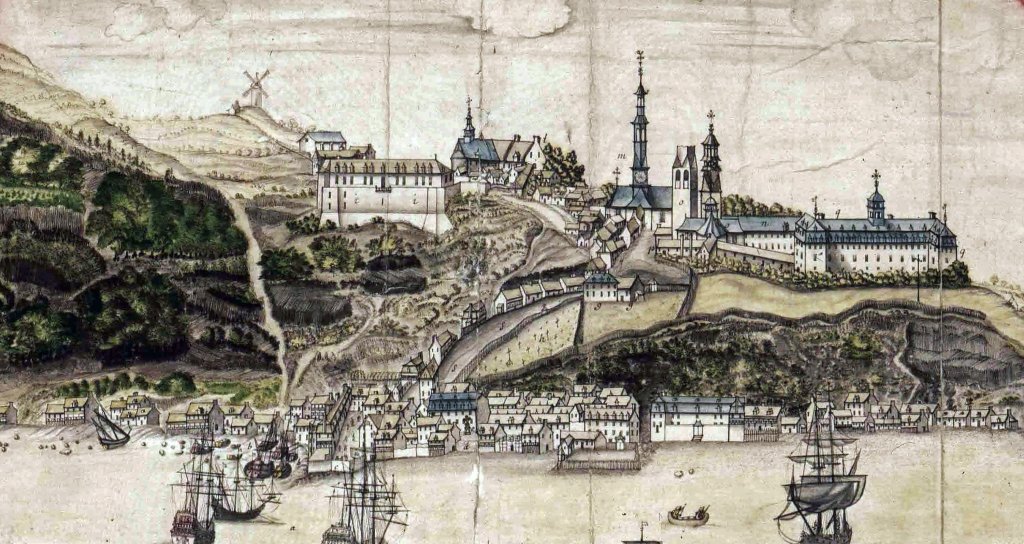

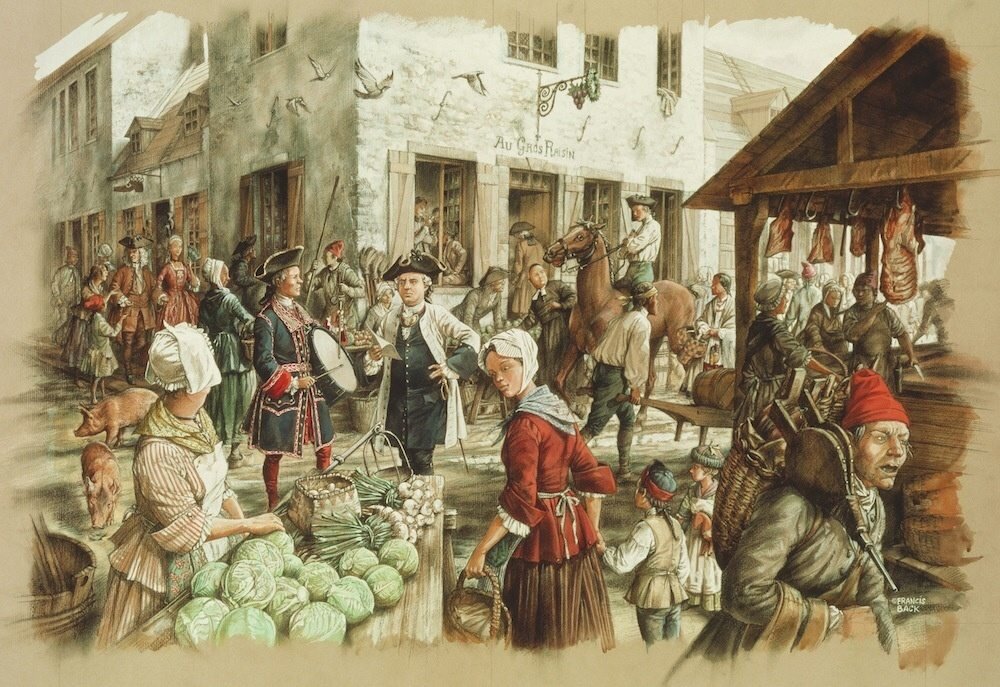

The farmer of early Canada payed small amounts in tenant dues and church tithes, fertile land was ready to be claimed at request, food was plentiful, and all were allowed to hunt and fish. By the 1630s the small colonies of Quebec and Montreal had grown into booming centers of trade and had turned into citadels of French power. The French clergy, seeing little success in converting the Indians, had turned back to the colonies and established schools, hospitals, and even a university (Jesuit College opened its doors in 1636, one year earlier than Harvard).

Houses for old people and orphans were built and a complex structure of courts and litigation operations was created. In 1640, 240 people lived in New France, but by 1685 the population had grown to 10,000. Montreal and Quebec were now bustling and popular colonial capitals.

The artist Cornelius Krieghoff, one of the most knowledgeable historians of early Quebecois culture, depicted the French Canadian people as laborious but joyful people. The winter, when beds of snow covered the fields and warehouses were filled with supplies, was the time when the Quebecois had their “fun”.

The French Canadians, very affectionate towards their children, usually socialized through family gatherings, card games, dancing and drinking parties. (By 1749 boozy horse-driving had turned into such an issue in Quebec that a harsh law fining intoxicated drivers six livres – about six dollars – was implemented). The only forbidding influence appeared to be the clergy, who strongly disliked dancing, cards, jewelry and even hair ribbons. In 1700 the almighty Bishop Laval strongly castigated Quebecois women for their decorative coiffures and improper attire, but his words largely fell on deaf ears.

In early Canada the French clergy were (and remained) the strongest force in society, having the power to excommunicate someone immediately. However, notwithstanding the constant disobedience of their congregation, for some reason the French clergy continued to be hesitantly tolerant and declined to start the witch-hunts that were so common in New England during this time.

Colonies and Clashes: While Jesuits kept evangelizing for Catholicism in Canada and while French colonists decidedly settled down, Samuel de Champlain and other French administrators had an immense issue with sustaining control over the new colony. There had already been many clashes with other governments over land.

For example, in 1627 the infamous Kirke brothers, English adventurers who supported the Huguenots in France, obstructed the St Lawrence Rover for three years and seized the fur trade from France’s chartered company: The Hundred Associates.

Meanwhile, Sir William Alexander claimed Acadia (Nova Scotia) for James VI of Scotland. Many disputes occurred until 1632 until the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye returned Canada and Acadia to France. Even though trade started up again and colonization continued steadily, an anxious France exercised more energy in working out its sovereignty.

New France’s government: The colonists continually and resentfully complained about New France – one of their problems being the absence of a central, authoritative government. Due to this, in 1647 a council made up of a governor, the Jesuit leader, and the Governor of Montreal was implemented.

Although it was the council’s job to keep watch over economic endeavours in the colony, this model ended up being ineffective. Due to this the Crown (under Louis XIV) took New France as its ward in 1663.

Two specific men were very important in bringing French Canada a firm, centralized government. The first was Jean Baptiste Colbert, a determined finance minister who strove to remodel French colonial policy by creating a new administrative organization. Colbert wished to turn New France into a province with a government akin to France’s. To achieve this he applied a new structure made up of a governor-general, an intendant and a superior council. The Bishop of New France was placed on the council but unfortunately often argued bitterly with the incumbent governor.

Comte de Frontenac: One of the more dramatic governors of New France was the Comte de Frontenac, who personally had great charm and was also exuberant and unprincipled. From the start of his tenure, Frontenac opposed Canada’s most powerful clergymen. About the Jesuits he said: “Another thing displeases me… this complete dependence of the grand vicar and seminary priests on the Jesuits, for they never do the least thing without their order.”

Frontenac complained of the omnipresent Jesuit spies, how they stuck their nose in family issues, and how they exercised an astonishing and unacceptable control over all the settlers. His lack of respect towards the Jesuits appaled New France.

At the same time, he ignored the belligerent presence of the British Hudson’s Bay Company and misjudged its importance in Canada’s future.

St Lawrence settlement: Jean Colbert’s restructuring of the colony provided New France with a strongly centralized government that was able to expeditiously solve day-to-day issues. Jean Talon, the second man to remold the quality New France’s government and the first intendant of Colbert’s model, immediately started to reorganize settlement and was able to attract thousands of new colonists, many being women.

Most of the population headed to three towns: Montreal, Quebec and Trois-Rivieres. Colbert and Talon wanted the settlers to permanently settle along the St Lawrence but several travelled into the interior (these adventurers ended up marrying Indian women and giving rise to the Metis, a half-French, half-Indian people).

The transience of the people was a major challenge to the settlement of New France – Colbert, believing that mobility harmed French interests, ended up strongly opposing western expansion. He then forbade French settlers from leaving the central colony and limited the fur trade to the areas of Montreal, Trois-Rivieres and Tadoussac. Colbert’s disregard for the western areas simply allowed the British to more strongly establish themselves in the New World.

Anglo-French competition: In the 1660s two disaffected trappers, Medard des Groseilliers and Pierre Radisson, determined to respond to the large costs of bring furs back to Quebec (as commanded by the colonial authorities) and the excessive taxes they had to pay on fur pelts. They escaped to New England and were accordingly sent to Britain. In London Groseilliers and Radisson convinced a circle of London merchants to take control of central Canada’s fur trade by creating the Hudson’s Bay Company, which claimed a monopoly on trade in all areas draining into the Hudson Bay.

New France ended up in a cumbersome position: with the Dutch and English-allied Iroquois to the south and the growing Hudson’s Bay Company to the north. Afraid to lose their new colony, the New France started to undertake expeditions to expel the English from Hudson Bay.

By the beginning of the 18th century, strife had grown, particularly in the east where New England farmers had their sights set on Acadia. For many years New France had to be alert in defending itself against new settlers and sending its armies on harsh, ravaging raids that reached as far south as Boston.

But in 1713 the Peace Treaty of Utrecht was signed and agreed upon, and North America was divided among the European powers. The French relinquished much of their territory, Acadia and Hudson Bay were given to the British and Article 15 of the treaty acknowledged British sovereignty over the Iroquois people and allowed them to trade with western Indians in customarily French areas.

Peaceful years: Although France was hesitant in honoring the treaty, the colony saw three peaceful decades. Due to this, Canada started to prosper – the debilitated fur trade boomed, and the population grew from 19,000 in 1713 to 48,000 by 1739; agriculture and fishing also prospered, and lumbering and fishing industries arose.

But English imperialist economic ambitions shortly emerged and resulted in renewed conflict between the colonial powers in 1744. Several minor battles followed until the declaration of war in 1756 between France and England which ended up being critical.

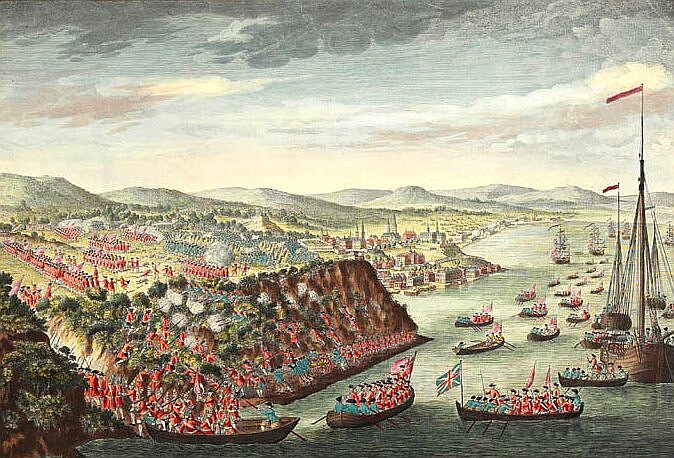

France, usually indifferent about its colony, sent the Marquis de Montcalm with a negligible amount of troops to Quebec. The general did not believe New France had much of a chance – defeat appeared to be unavoidable due to a shortage of troops and food supplies. Besides, France would rather not send its fleets to North America since this would put the mother country at risk. How did Montcalm think he would be able to defend New France’s long and sparingly guarded frontier?

New France’s defeat: To both countries, Quebec appeared to be the war’s key factor. In 1759 an army led by General James Wolfe started an advance. Montcalm, counting on the city’s naturally strategic location (atop lofty cliffs) allowed the invaders to come to him. After many failed frontal attacks, one of Wolfe’s men recommended a side attack. On September 12 at night, Wolfe and his soldiers crossed the St Lawrence River hidden by the darkness and surmounted the cliffs. The French, totally off guard, drove back the British but became frightened and quickly retreated (not knowing that their enemies were also afraid and about to retreat). Wolfe was killed in the battle and Montcalm suffered mortal wounds.

After Quebec fell it was only a matter of time before the British conquered the rest of New France. By 1763, the Treaty of Paris transferred France’s Canadian territories to England.

Leave a comment