The wake of the War of 1812 instilled in Canadians new feelings of dynamism and self-determination. As the economy prospered, settlers in Upper Canada started to take a closer look at Britain’s political and economic place in the colonies. Similar inquiries were being made in Lower Canada but for separate reasons: French Canadians bitterly criticized the British due to extensive unemployment and rising poverty.

Canadian settlers were primarily dissatisfied with their colony’s political structure. Despite the Assembly’s nature as an elected body, resolutions passed in this elected legislature were often overridden by a Council chosen by the king of England with executive powers. The patronage, corruption, and privilege upset Canadians, who started to advocate for Responsible Government, particularly an elected Council.

The uprisings: In Quebec the Council (called the Chateau Clique) incurred most of its criticisms from the vitriolic Louis-Joseph Papineau, the Patriote Party’s father. The patriotes came up with a list of 92 resolutions and called for the abolishment of the chosen Council as their main complaint.

Britain unconditionally rejected their desires. Finally pushed beyond their breaking points, the patriotes headed to the streets and fought with British soldiers. The insurrection was put down after many deaths and the party lost its leader when Papineau escaped to the United States.

In Upper Canada the struggle for Responsible Government was led by William Lyon Mackenzie, an impassioned Scotsman who served as the publisher/editor of a local newspaper. Mackenzie, renowned for his fierce attacks against the Family Compact (the name for Upper Canada’s Appointed Council) had earned election to the Assembly in 1828 but was removed in 1831 for libel.

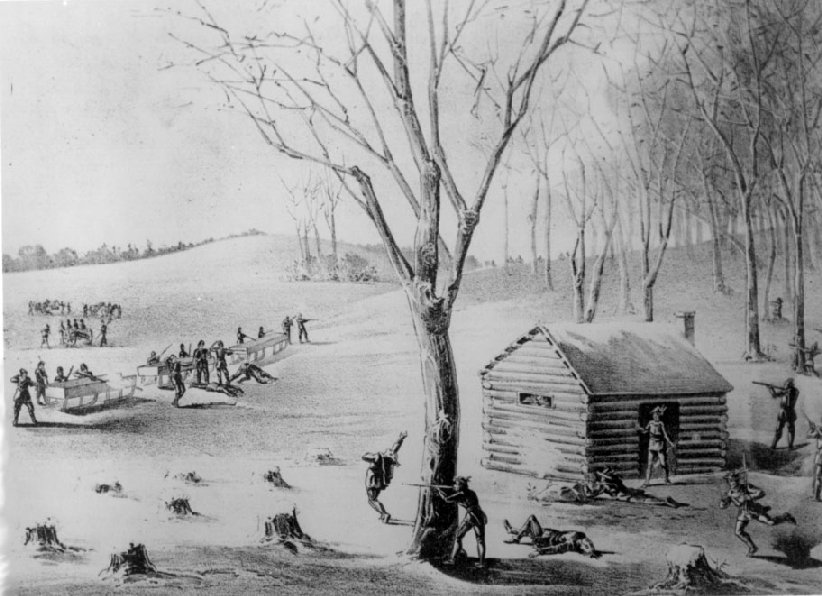

In 1837 Mackenzie gathered hundreds of angry protesters in Montgomery’s Tavern on Toronto’s Yonge Street. After some drinks of whisky, dissatisfaction turned into active protest and the band of insurgents marched towards the government edifices. 27 armed troops waited for them there. When a Colonel Moodie fired at the renegade blockade, he was killed by retaliatory fire. The misadventure so rattled the protestors that they frantically took flight, Mackenzie heading to the United States.

Despite many Canadians agreeing with the protestors, Britain took a harsh stand against the uprising. The hanging of two leaders of the Upper Canada uprising did not stop the growth of annoyance with British governance. John Ryerson wrote this about the execution: “Very few persons present except the military and ruf scruf of the city. The general feeling is total opposition to the execution of these men”.

The Durham Report: But Britain understood that reforming the colony’s obsolete constitution was necessary. A royal commission was created to examine the issues. The man selected to head the group was a politician and a member of one of the richest English families, dubbed “Radical Jack” by his colleagues. A man with a morose intensity and a hot temper, Durham was chosen as Governor General.

After investigating for six short months, Durham headed back to England to produce his report on the “Canada issue”. In the document, Durham complained of the stagnation in the five colonies and suggested that Canada create a workable economy to exist beside the energetic and assertive United States. He believed that unifying the colonies into one province would be good for creating this economy.

Durham also thought that this union would reduce the current hostility between the English and French settlers by absorbing the latter into conventional British culture. French culture (which Durham discreetly believed was fundamentally “backward”), according to the report, was impeded by French colonial policies.

Notwithstanding the report’s conspicuous ethnocentrism, it did advocate Responsible Government for Canadians. Britain followed but changed some of Durham’s recommendations, uniting Canada West and Canada East and allowing each area equal representation in a common legislature. In 1849 the new legislature created a government for the Province of Canada.

The origins of Confederation: The belief that Canada would always be threatened by American or British domination while the colonies stayed separate areas penetrated political thought in the 1850s and early 1860s. Confederation, an idea that had been talked about for almost a century, soon reemerged as a feasible possibility.

After self-government was won, politics became regional – for nearly a decade business in the Assembly revolved around minor political squabbles. Affairs like the seriousness of building an intercolonial railway and the need to obtain new territories were ignored due to clashing party interested.

Governments survived for a few months, then a few weeks, before in 1864 a political deadlock in the Assembly occurred. The American Civil War raged in the south, and Canadians were disturbed by the possible restarting of Anglo-American conflict. Confederation appeared to be an opportune way to set the colonies on a dynamic path. The deadlock happened in the same year that a rare coalition of rival parties (George Etienne Cartier’s Blues, John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives and the strong newspaper mogul George Brown’s Liberals) was created. The idea of their union was the realization of Confederation.

Similar talks on the unification of the coastal provinces had begun in the Maritimes. The Atlantic provinces had already set up a conference to develop a strategy for Confederation, when word of their plans reached the governments of Upper and Lower Canada. A delegation made up of John A. Macdonald, George Brown and six other ministers decided to butt in on the conference and share their own proposals.

The Queen Victoria was hired in Quebec City and, packed with $13,000 worth of champagne, headed for Prince Edward Island. Even though they felt kind of rattled by being met by a sole official in an oyster boat, the delegation ended up convincing the Maritime governments to add Upper and Lower Canada to Confederation. Confederation’s rough terms were developed at “the great intercolonial drunk” (called this by one dissatisfied New Brunswick newspaper column) and was given confirmation at the Quebec Conference a few weeks later.

Confederation Canada was realized on July 1, 1867 when the British North America Act split the British Province of Canada into Ontario and Quebec (originally Upper and Lower Canada) and merged them with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The new country was named the Dominion of Canada.

The British North America Act, 1867:

Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom:

And whereas such a Union would conduce to the Welfare of the Provinces and promote the Interests of the British Empire:

And whereas on the Establishment of the Union by Authority of Parliament, it is expedient, not only that the Constitution of the Legislative Authority in the Dominion be provided for, but also that the Nature of the Executive Government therein be declared:

And whereas it is expedient that Provision be made for the eventual Admission into the Union of other parts of British North America.

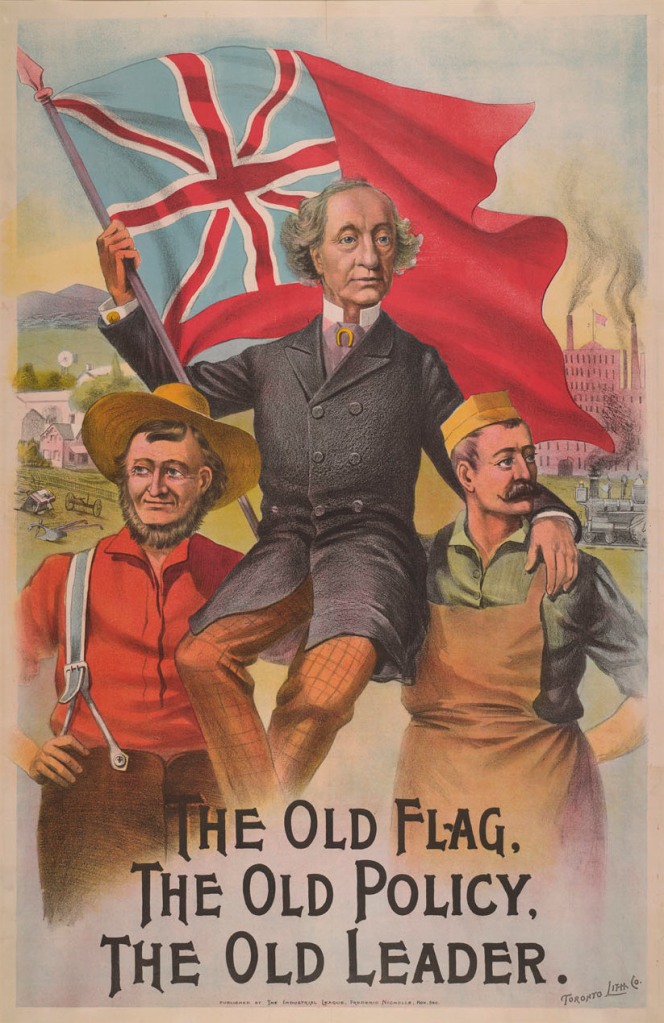

The effort for leadership: The unlikely hero of a unified Canada was John A. Macdonald, a man who was formerly against the idea of Confederation when it had been put forward by Alexander Galt and George Brown, but who would become the first Prime Minister of the dominion. Born in Scotland in the same year Napoleon lost Waterloo, and accompanying his parents to Kingston, Ontario while still a little boy, Macdonald may have been the most unconvincing person in public life to foster a young Canadian country.

Macdonald was tall and lanky with a bloated nose and an irresponsible but edged sense of humour. He appeared to be contrary to the expected picture of a Canadian Prime Minister. He did not have the uptight restraint of a British politician. But Macdonald made up for his deficiencies in deportment and appearance with his acute intelligence and penetrative abilities of insight. Never running out of words, Macdonald showed Canadians an important qualification for Prime Minister: wit, eloquent attack and refutation.

Notwithstanding this refined image, Macdonald suffered tragic misfortunes in his personal life. He met his cousin Isabella Clark on a trip to Scotland and married her, but shortly after her health declined. In his first year as a politician, Macdonald had to juggle between attending vehement arguments in the Assembly in the day and heading home at night to see his wife slowly dying.

Isabella finally died, and nine years later Macdonald married Susan Agnes Bernard, and had a mentally disabled daughter with her. Influenced by contemporary attitudes, this incident would traumatize Macdonald for the rest of his life.

The Metis uprising: Confederation did not move forward unproblematically after being accepted by London. One of the first problems was the obtaining of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000. The government misguidedly conceived the territory as the solitary possession of the Hudson’s Bay company and failed to consider the indigenous inhabitants, particularly the Metis of the Red River Colony. This created problems.

The Metis were Francophone Catholic nesters (called “half-breeds” by the disdainful British) who had long seen themselves as a sovereign but autonomous nation that was of neither European nor Indian origin. When Rupert’s Land was obtained without their approval, the Metis banded together with Louis Riel, a man of magnetic fluency, as their leader. The Metis took the British outpost of Fort Garry and formed a provisional government.

No one was killed during the rebellion. Backed by an American fifth column of infantrymen, the Metis had a powerful case, and the Macdonald government accepted this. Negotiations had begun and they may have concluded peacefully if a young arriviste, Thomas Scott, had not attempted to strangle Louis Riel. Riel had the prisoner put on trial and shot.

Macdonald was appalled because Scott had been an Ontarian citizen; even worse he was a Protestant killed by a Catholic. Unsurprisingly the matter became politically “delicate”. It was eventually solved when the colony joined the Confederation as the province of Manitoba. Riel escaped to the United States.

Despite its reassurances, the Canadian government failed to respect the Metis community’s integrity and over a decade after the first insurrection, Riel returned to start a second one, now in Saskatchewan. Finally captured by British troops, Riel was tried as a traitor. Maybe Macdonald’s darkest stain in his otherwise renowned career was his choice to hang Lois Riel. In response to outraged French cries of protest, the Prime Minister commented: “He shall hang though every dog in Quebec should bark in his favour.” Riel’s death only embedded the old, bitter resentment between the French and the English.

Scandal: MacDonald suffered another stain on his political record through the Pacific Railway Scandal, an occurrence that threaten to severely impede the Dominion’s growth. Prince Edward Island, the Prairies and the Pacific Coast had joined Confederation by the time of Canada’s second election. An important issue in the 1872 elections was the trouble of connecting the provinces and maintaining links among them. The common sense solution appeared to be a national railway extending from coast to coast. The Canadian Pacific Railway was an endeavor put forward by Macdonald’s party and was masterminded by Sir Hugh Allan, a renowned Montreal shipping mogul. But the railway was supported by large American investments and Macdonald brusquely informed Allan that the project cannot include foreign capital. Allan accepted these conditions but tricked Macdonald by keeping his American partners but hiding them behind the scenes.

Six weeks before the election day, Macdonald found that he needed campaign funds; he requested some from Hugh Allan. Strangely, $60,000 appeared; quickly followed by another $35,000. Macdonald wired Allan for one last amount in a moment of calamitous recklessness: “I must have another ten thousand. Will be the last time of calling. Do not fail me.”

Macdonald and his party emerged victorious in the election, and Sir John could relax for the first time in several months. But during his relief, others planned against him. A confidential clerk looted the offices of Sir Hugh Allan’s solicitor late one night, and stolen documents were sold to politicians of Macdonald’s opposition party, the Liberals, for the small amount of $5,000.

The Liberals leaked the scandal: it appeared that Prime Minister Macdonald had offered the Canadian Pacific Railway project to Hugh Allan in exchange for election finds. To prove the story, the front pages of the newspapers printed the revealing telegram – “I must have another ten thousand” – the next day.

Finally made to resign, Macdonald left his position in dishonor. The railway would later be finished but it was always missing the splendor of accomplishment that Macdonald had dreamed of so often.

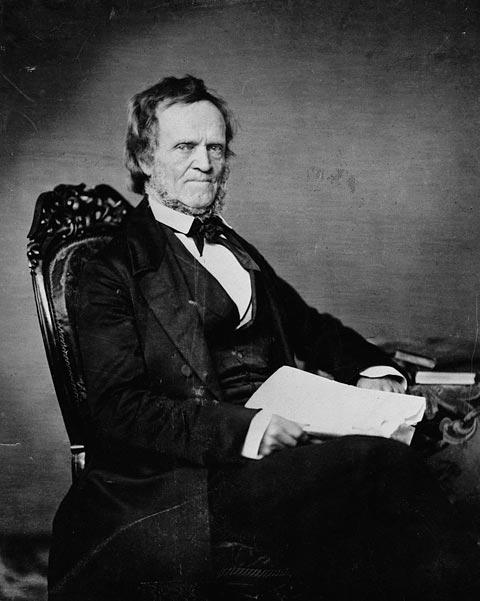

The end of a century: When Macdonald vacated his position, Alexander Mackenzie took up the job of influencing Canada’s future. Macdonald then returned as Prime Minister for more than a decade and others followed him: Sir John J. Abbott, Sir John S.D. Thompson, Sir Mackenzie Bowell, Sir Charles Tupper. When 1900 came, Canada was on a hopeful path as a nation. Constantly confronted with new challenges and negotiating different interests, Canada saw the coming of the 20th century as the start of a promising, golden future.

Leave a comment