Location

St David’s is in the region of Deheubarth in the southwest of Wales. It is a remote corner on the coast of the Irish sea, with rocky and barren soil without woods, rivers, or meadows, never exposed to the winds and tempests.[1] The cathedral is in a narrow valley with damp, marshy and unstable ground at the bottom.[2]

St David’s Cathedral (image from 1585-86 since medieval images of cathedral are rare. But the general cathedral appearance was very similar)

Cathedral History

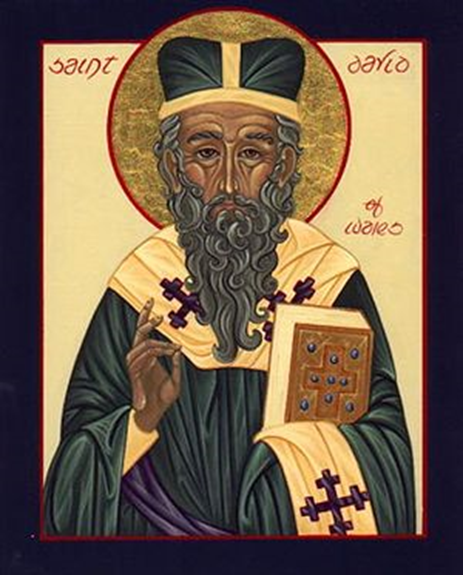

St. David’s was originally established in the sixth century as a monastic community and church called Menevia by Saint David. He was the successor of Dyfrig, archbishop of Caerleon. David moved the seat to Menevia.[3] Miracles occurred during his life, among them the elevation of the ground beneath his feet during a sermon, creating a hill. This foreshadows the miracles later seen by some pilgrims visiting the site.[4]

St David, Archbishop of Menevia

It is said that a later successor named Samson was forced to flee Dyfed due to the “yellow plague” with the pallium. But this was a story to elevate St Davids and to explain why there were no official documents confirming it as an archbishopric. The chronology makes it impossible: Samson was really a contemporary to St David. [5] William the Conqueror went on a pilgrimage to St Davids in 1081, close to the ending of Deheubarth’s independence in the early 12th century. The Anglo-Norman bishops since then have respected the status of St Davids and its patron saint. Pope Calixtus canonized David and declared that two pilgrimages to Menevia were equal to one to Rome. St. David later became popular as a pilgrimage centre, made clear by its Welsh name Tyddewi or “David’s house”.[6]

Wales currently does not have a native bishopric but is under the metropolitan at Canterbury.[7] Both the first Norman Bishop Bernard and Gerald of Wales have attempted to elevate St. Davids to metropolitan status. Bernard was so driven by conviction for his goal that he sometimes carried an archbishop’s cross before him during his travels through Wales. Although Bernard failed to make St Davids an archbishopric, and his successor David Fitzgerald was made to stop this goal, he left behind a Welsh diocese.[8] The English feel that a Welsh bishopric will threaten their authority. The conquest of Ireland in 1169-70 made St Davids more connected, as the nearby coastline provided the main departure points for the voyage across the Irish sea, and a royal expedition to Ireland in 1171-2 saw Henry II visit the town twice.[9] Either the enthusiasm for David’s vision or the extent of his cult’s influence, or both, could explain Bishop De Leia’s decision to renovate the church. Lord Rhys ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales, was a patron of this project, and he has recently been buried here.[10] Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury visited St Davids in his 1188 tour of Wales with our esteemed cleric and historian Gerald of Wales to preach the crusade but also to assert Canterbury’s supremacy. He said high mass on the altar. De Leia died in 1198, and the church will be completed in 1210. [11] St. David’s is precious to Gerald, and he has attempted to become his bishop. His desire for the archbishopric is greatly connected to his own identity as a Welshman, as he laments the loss of St Davids and the Welsh Church to the Anglo-Saxon invasion. But Gerald has not succeeded despite travelling as far as Rome.[12]

Cathedral architecture

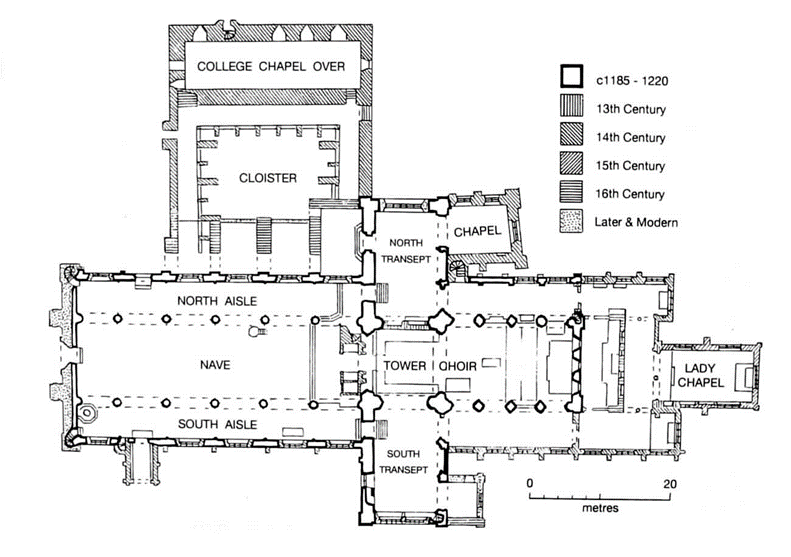

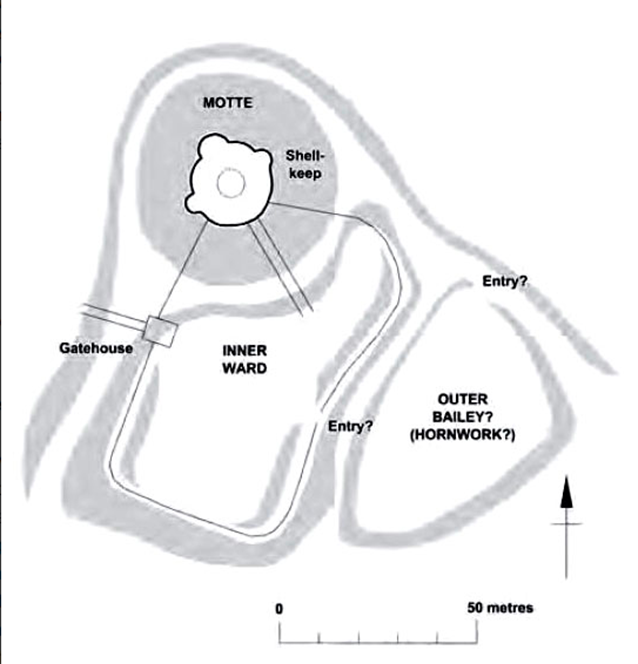

St Davids chronological plan (only focus on first one)

Bishop Peter de Leia’s 1182 design consists of an aisled nave of six bays, along with a choir of four bays, a central tower, and transepts. The roof is made of timber.[13] The nave was erected between 1182 and 1198.[14] The nave and its six opulently decorated and widely spaced arches are nearly homogenous.[15] The triforium and clerestory are combined.[16]

St David’s Cathedral nave

St David’s has one of the best displays of chevron in Britain, using a diverse arrangement of patterns. Eleven different patterns of chevron were used on the main arches, and the upper levels have 24 decorated arches, providing a luxurious atmosphere. The chevron is in color, dominating the cathedral appearance.

The nave has been designed for sexpartite vaulting.[17] It has a stone tufa high vault. There are wall arches or formerets to define the edge of the vault. The mortar used for the high vault was of excellent quality, holding the web in place next to the wall in the three western bays. Tufa vaults have been tradition in the West Country for a century. [18] The tufa from St Davids was imported as there are no local deposits. Aisle vaults were also built.[19] The vaults take a domical form. The responds and walls ribs were provided for the vaults, which were only inserted when the church was finished and roofed. The springer blocks of the aisle vaults are built into the wall over the capitals.[20]

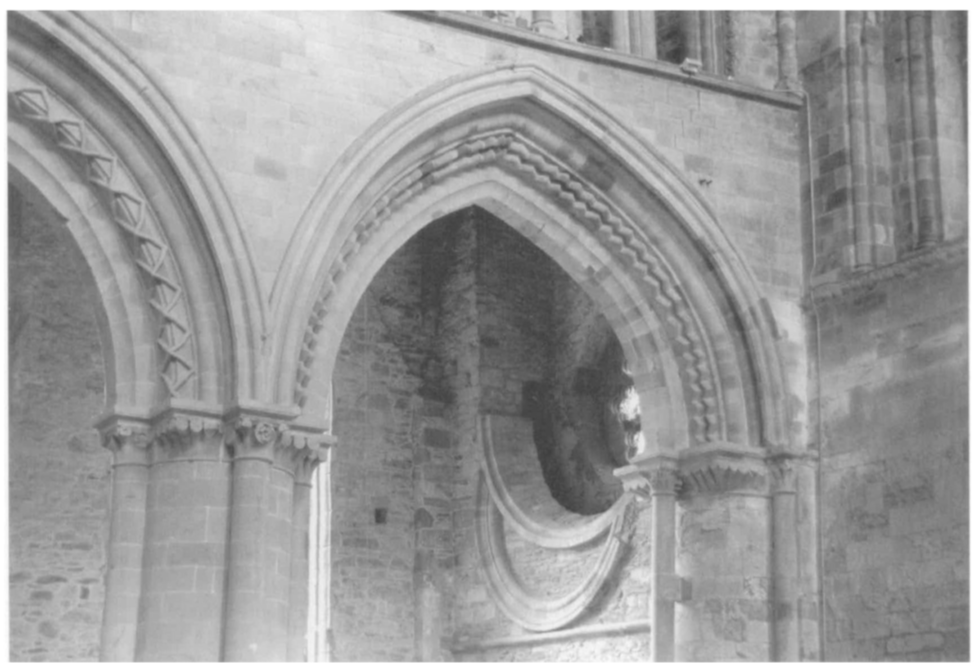

The old structure is connected to the new church, and an ancient church consecrated to St. Andrew lay on the area of the north transept chapel, now the Becket chapel.[21] The west wall’s responds were detached, the only area where this occurred. The arches of the south arcade were constructed in one campaign, but the arch stones of the north side were made later. The piers began to lean west during construction, and in the west bay the walls had to be built from ashlar masonry rather than coursed rubble due to its proximity to the river. There is a rose window at the west end of the south aisle.[22]

Western bay of south arcade in St Davids nave with rose window and detached shaft on west respond

St. Davids’ piers alternate between octagons and cylinders. But the combination of this alternation and the pilier canton makes St Davids stand out. This pattern was repeated in the choir.[23] The nave is two times the length of the choir, so the only way to leave enough space for the sanctuary and high altar was to place the stalls under the crossing tower.[24] There are two chapels west of the cathedral dedicated to St. Patrick and St Justinian, since before St David arrived the site was associated with them.[25] West country masons from South Wales worked on this building, bringing their style.[26]

Weather and when to visit

South Wales, in particular Pembrokeshire, has a pleasing weather due to its flat plains and sea coast.[27] Even in winter it does not snow in South Wales. The healthy air from Ireland also tempers the climate.[28] This is the reason why this area of Wales has a bigger population and is more open to the outside world than the rest of the country. But visiting in the spring or the summer may be better because of the sun and because there will be less storms ravaging the coast of Wales.

What to wear and pack

Bring combs and small knives to cut your hair. The Welsh of both sexes cut their hair close round to the ears and eyes, while the women cover their heads with a large white veil folded together like a crown. Both sexes brush their teeth with white hazel, making them look like ivory, and then wipe them with a woolen cloth. The men shave their whole beards except the moustaches, and sometimes they cut their hair. Some even anoint their face with a nitrous ointment.

The Welsh only wear a thin cloak and tunic, even in the cold. [29] But if you aren’t used to it, you may want to wear some wool. If you are a warrior, bring light arms which do not harm your agility, small coats of mail, arrow bundles, and long lances, helmets and shields, and if you can greaves plated with iron. The higher-class rides on fast horses, but most people fight on foot due to the marshy and uneven soil, so depends on your class. They either walk bare-footed or use high shoes.[30]

If you are a pilgrim, it may be a good idea to wear a pilgrim’s cloak and to use a staff to help you traverse the difficult areas of Wales. It would be a good idea to have some coins handy, perhaps two pence to sixpence to ensure you will be able to cover any fees for travel. You may also want to offer something to St David’s for your pilgrimage there. A horse may come in handy although not all the terrain is necessarily well suited for one, so it depends on the path you are taking. If you want a horse, you may use your own or a hired one.

Getting around

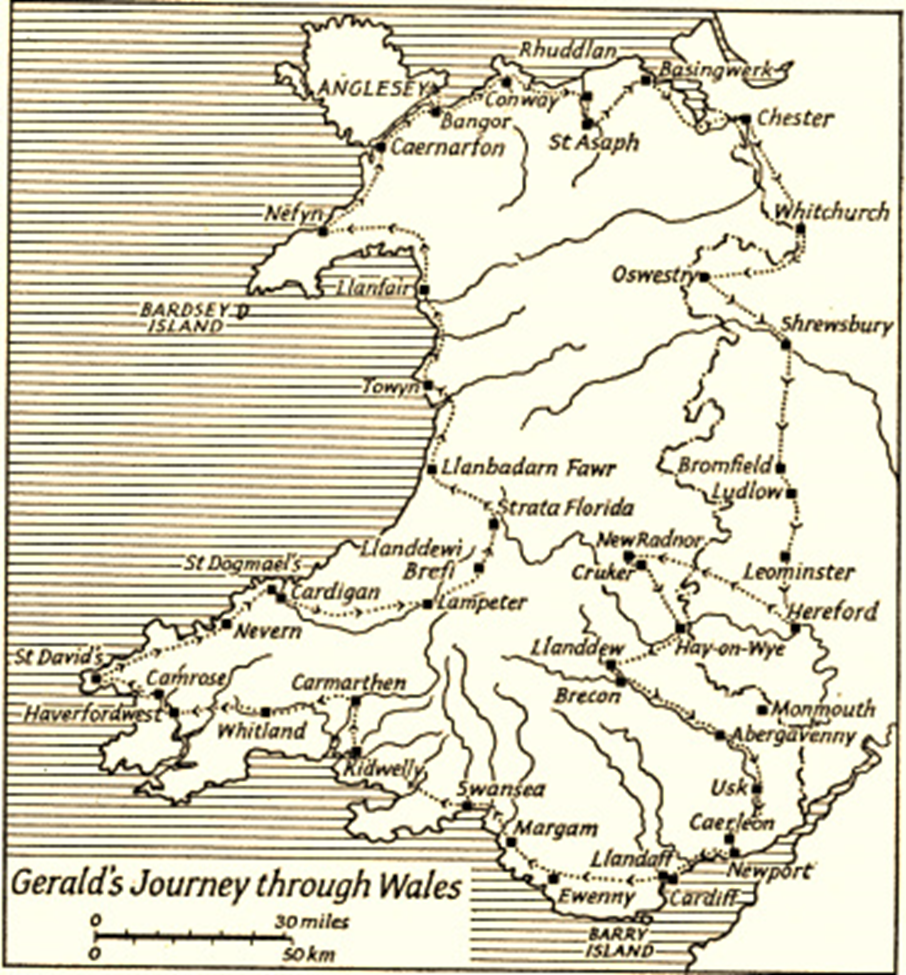

Gerald of Wales Journey with Archbishop Baldwin, 1188 (focus on path to St David’s from Carmarthen).

The marshy and uneven soil of Wales may make it more convenient to walk on foot rather than ride a horse. Coming from the east, you may traverse the low ground of South Wales hugging the coast of the Severn Sea. Then you will cross the river Tywy, Wales’ longest river, preferably in a boat.[31] You will then have to cross the river Taf and Cleddeu, under Laindwaden, and then another branch of this same river before getting to Haverford.[32] Pembroke is to the southwest while St David’s is to the northwest.

The road will take you through the village of Camros, then down to Niwegal sands bordering the Irish Sea. But beware, for there may be a tumultuous storm, especially if it is winter.[33] If you are entering the northern side of the church from the cemetery, you will walk over the marble stone Lechlavar, meaning “talking stone” in Welsh, which serves as a bridge over the muddy river Alun. But you may want to make sure you’re not bringing any corpses, for it is said the bridge may speak and crack! If you are coming from Ireland, the passage from the Irish Sea is easy and may be accomplished in one day.[34]

Also always keep your head up and guard your possessions and person! Acts of robbery, plunder and theft are common in Wales and can affect native Welshmen as much as foreigners.[35]

Sites to see

Lechlavar is an attraction on its own. When he returned from Ireland, Henry II passed over Lechlavar. Clothed like a pilgrim and leaning on a staff, and heading towards the shine of St David, he met the church canons at the white gate. Merlin predicted that a King of England returning from St David’s would die upon Lechlavar. Henry walked over the stone, but nothing happened, revealing that he would not conquer Ireland. Indeed, he never did. The jackdaws of St David’s are domesticated and tame. The mountains of Ireland can be seen from there in clear weather. [36]

Carmarthen means city of Merlin, as he was born there from an incubus. The city is on the banks of the river Tywy, with woods and pastures around it, bordered with brick walls, half of which still stand, with Cantred Mawr on its eastern side, a haven due to its thick woods. There also stands the castle of Dinevor on a tall summit above the Tywy, and the seat of South Wales’ princes. On the other side of Tywy, in the Cantref Bychn, or little cantred, there is a spring which ebbs and flows twice daily. Saint Clare is a long, straggling village at the junction of the rivers Cathgenny and Taff. Immediately on the former’s banks stood the castle. [37]

Carmarthen Castle plan from 1181-1222 according to N. Ludlow

Haverford is a town on the river Cledheu, with a large and commanding castle. The residents of this province are from Flanders, sent here by King Henry I. They are brave and hardy, hostile to the Welsh, skilled in commerce and manufacturing wool, and well suited for the plough or sword. [38] The Flemings look at the boiled right shoulders of rams for divination. Through this method it was found that Wales would be invaded and destroyed after King Henry I’s death, a year and a half before the event, and the people sold all their possessions and escaped.[39]

Pembroke is a province joined to the south of the territory of Ros, in Demetia, South Wales, separated from it by an arm of the sea. Its main city is placed on an oblong rocky eminence, extending with two arms from Milford Haven. Arnulph de Montgomery, in the reign of King Henry I, built here a thin fortress with strakes and turf, and gave it to Gerald of Windsor when he returned to England.[40] The fortress of castle of Manorbier is three miles from Pembroke. It is on the top of a hill extending on the western side to the sea port, defended by turrets and bulwarks. There are fish ponds below its walls on the northern and southern sides, along with an orchard bordered by a vineyard and a wood. To the west, the Severn sea, heading to Ireland, enters a hollow rocky bay some space away from the castle.[41] It also has large falcons, which king Henry II loved and collected.[42]

Model of late 12th-early 13th century Pembroke

Camros, between Haverford and Menevia, is not remarkable except for a large tumulus, but the road to St David’s leads through there, before descending to Niwegal sands. Sometimes violent storms reveal ancient tree trunks in the very sea itself, turning the soil black like ebony. When this occurs, road for ships can be blocked, and many sea fish may also be sent upon dry lands. Many parts of the Wales coast have remains of ancient forests, especially the north.[43]

Where to stay

The houses of Wales are common to all, and they consider liberality and hospitality to be important virtues. On entering any house, you must only relinquish your arms if you enter a house. When water is offered to you, allow your feet to be washed if you want to be received as a guest. But if you do not want it, you may prefer morning refreshment instead than lodging. The young men move around in troops and families under a chosen leader’s direction. They have free admittance to any house as they defend the nation. So try to join one of these.

Those arriving in the morning are entertained with young women and harp music. In the evening the meal is prepared depending on the number and dignity of the people there and the family’s wealth. The dishes are placed on rushes and fresh grass, in big platters or trenchers. The host and hostess pay attention and take no food until their guests have. After this, a bed made of rushes and covered with a coarse type of cloth made in the country, called Brychan, is placed along the side of the room, and all the people sleep there.[44]

The Bishop of St David’s may give you lodging. You may also want to go to Manorbier, where Gerald of Wales will receive pilgrims heading to St David’s, especially ones who are as interested in the topography and history of Wales as he is.

Cuisine

Wales is considerably supplied with corn, sea-fish, and imported wines.[45] Almost all of them eat the produce of their herds: oats, milk, cheese and butter, and eat more flesh than bread.[46] They also eat a thin and broad bread cake which is baked every day, called lagana. The Welsh desist from hot meats and only eat what is cold, warm or temperate so that they can be healthy. Sometimes meat with chopped broth is added. [47] The Welsh also like to drink beer, especially that made from barley, and ale.

The territory is home to flocks of sheep, and some graze on seaweed around the seashore. The special meat of this lamb bas a buttery texture and genteel well-rounded taste. Lamb is such a special meat in Wales that it is only eaten on high days and holidays. The pig is the family’s basic meat. Fresh garden vegetables, fish from the rivers, lakes or sea, and meat from the family pig form the basis of the land’s cooking. Beef features prominently along with freshly caught fish like salmon, brown trout, white crab, lobsters and cockles. The classic broth soup called cawl is made of bacon along with leeks and cabbage, two of our basic vegetables. This one-pot dish, cooked in an iron pot above an open fire, uses all Welsh ingredients: lamb, cabbage, swede, and leeks. The recipe varies from region to region and season to season, depending on what vegetables and produce can be found.

An edible seaweed known as laver is gathered and processed, and is eaten on laverbread, which is sprinkled with oatmeal, heated in bacon fat and served with bacon for breakfast or dinner. Cheese soaked in brine is another favorite.[48]

Local customs: In musical concerts Welsh singers do not sing simultaneously like in other countries, but in several different parts, so that there will be heard different parts and singers, who at length will all unite, with organic melody, in one harmoniousness and the soft sweetness of B flat. On the borders of Yorkshire past the Humber, the inhabitants also sing in a symphony’s harmony, but with less variety, singing on merely two parts, one murmuring in the base, the other trilling in the acute or treble. The two nations got these talents naturally through long habit, and even the infant children sing like this. Danish and Norwegian invaders may have influenced the natives in this form of singing and speaking.[49] The Welsh use harps for music, and each family believes that playing the harp is preferable than any other learning.[50] They play their musical instruments sweetly and quickly yet keep the musical proportions. Entering a movement, they complete it with delicate animation and loose frivolity. As it is a pleasure to those who understand, the music is confusing and fatiguing to those who do not. Three instruments are used: the harp, the pipe, and the crwth or bowed lyre.[51]

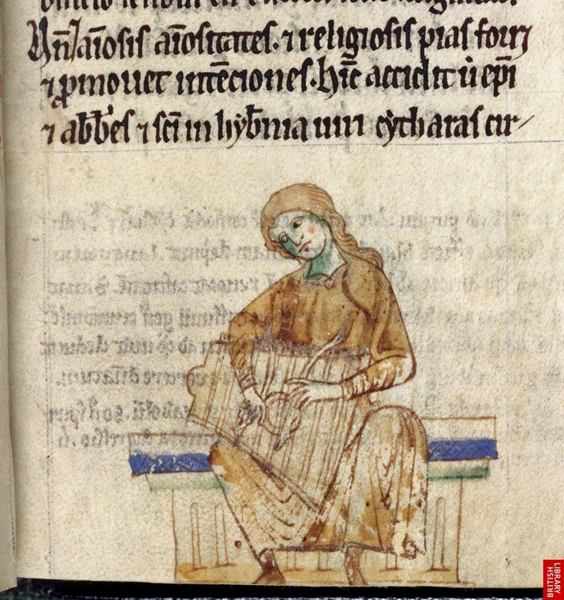

Lady playing a Harp, Topographia Hibernica

The Welsh have a strong warrior culture and often raid the Marches. The bards and poets the Welsh esteem encourage battle against Marcher lords, and write poems proclaiming the value of warrior kings, honor and death in battle. The bardic culture unifies the Welsh with shared traditions and a mythic past.[52] Violence is a way of life for the Welsh since there is a lack of central government. [53] Poems and stories are offered as the evening’s entertainment in the halls, delighting and serving as propaganda for princes. The Welsh express their history through literature and poetry. [54] The leaders of Welsh society are hard-drinking and lustful warriors, triumphal in prowess, sensitive of their honor, and conditioned by a social code preaching the need for vengeance and the shame of dishonor.[55]

Welsh warriors, manuscript from 1280s

Gwion Bach was a servant in the household of Tegid Foel and Ceridwen. He was eaten and sent adrift by the latter for stealing her potion but was reborn as the poet Taliesin. He later saves Gwyddno, squire of King Maelgwn, from his own king’s wrath. This story shows the benefits for a person who is kind to his poets. Poets are depicted as honorable holders of truth, loyal and with magical abilities.[56]

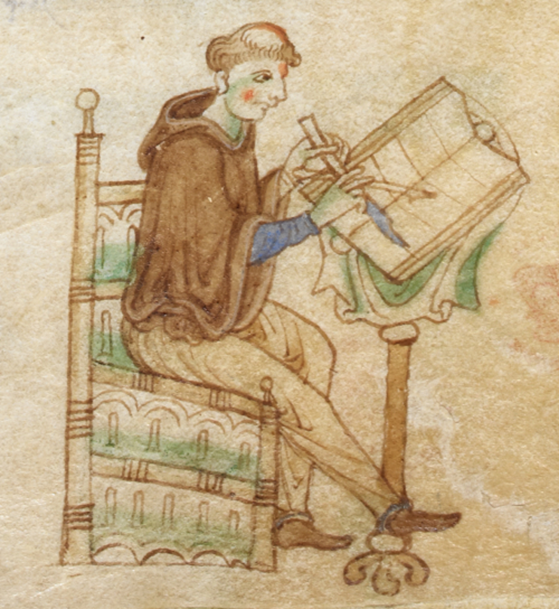

Medieval Scribe writing a manuscript from Gerald of Wales’ “Topographia Hibernica“

The Welsh have many problems. Walter Map is an esteemed Welsh writer who like Gerald of Wales is conflicted on his countrymen. He criticizes them as completely unfaithful to all. If they may seem charitable in one respect, in most they appear bad-tempered and cruel.[57] The frequent Welsh raids color Maps’ unfavorable views. He believes they have no fear of God.[58] Gerald of Wales adds that the Welsh will often take false oaths in order to obtain advantages. They are a cunning and crafty people: in civil and ecclesiastical causes, each party will swear what is advantageous to it, there is always a bias for the accuser against the accused.[59] Walter disliked the court life of Henry II and used Welsh stories to satirize it. This is made clear when he likens the court to hell and asks what hellish punishment does not multiply there.[60]

We hope you’ve enjoyed your trip to late 12th century St Davids and Southwest Wales!

[1] Gerald of Wales, The Itinerary of Archbishop Baldwin through Wales (Oxford, Mississippi, 1997). 95.

[2] Jonathan M. Wooding, “Recent Research at St Davids Cathedral,” Archaeological Journal, vol 167, (2010). 60

[3] Karen Stöber, “An Ecclesiastic Identity in the Making: The Medieval Cathedral and Bishopric of St David’s (Wales),” Imago Temporis. Medium Aevum XIV (2020).186.

[4] Ibid, 197.

[5] Ibid, 189.

[6] Richard Suggett, “St Davids Cathedral,” Archaeological Journal, vol 167, (2010). 56-57.

[7] Stober, “Ecclesiastic,” 188.

[8] Ibid, 190-92

[9] Roger Stalley, “The Architecture of St Davids Cathedral: Chronology, Catastrophe and Design.” The Antiquaries Journal, 82 (2002). 17.

[10] Wooding, “Research,” 59-60.

[11] Stalley, “Architecture,” 17-20

[12] Stober, “Ecclesiastic,” 193.

[13] Suggett, “Cathedral,” 57.

[14] Stalley, “Architecture,” 25.

[15] Ibid, 21.

[16] Ibid, 34.

[17] Ibid, 30-31.

[18] Malcolm Thurlby, “Did The Late Twelfth-Century Nave of St Davids Cathedral Have Stone Vaults?” The Antiquaries Journal 83, (2003), 443.

[19] Ibid, 45.

[20] Stalley, “Architecture,” 38-39.

[21] Ibid, 41.

[22] Ibid, 22-24.

[23] Ibid, 30.

[24] Ibid, 25-26.

[25] Stober, “Ecclesiastic,” 195-96.

[26] Stalley, “Architecture,” 13.

[27] Gerald of Wales, The Description of Wales (Oxford, Mississippi, 1997), 164.

[28] Gerald, Itinerary, 85.

[29] Gerald, Description, 170-71

[30] Ibid, 167

[31] Gerald, Itinerary, 73.

[32] Ibid, 76.

[33] Ibid, 91.

[34] Ibid, 100-1.

[35] Gerald, Description, 190.

[36] Gerald, Itinerary, 99-101.

[37] Ibid, 73-75.

[38] Ibid, 76-77.

[39] Ibid, 80-81.

[40] Ibid, 82.

[41] Ibid, 85.

[42] Ibid, 90.

[43] Ibid, 91-92.

[44] Gerald, Description, 168-70

[45] Gerald, Itinerary, 85.

[46] Gerald, Description, 166.

[47] Ibid, 169-71.

[48] Ben Johnson, “Welsh Food – Traditional cooking, food and recipes from Wales,” Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Traditional-Welsh-Food/

[49] Gerald, Description, 174-75.

[50] Ibid, 169.

[51] Ibid, 172.

[52] Sarah Lynn Anderson, “A Land of Poets and Warriors: The Connection Between Warrior Culture and Bardic Culture in Medieval Wales c. 1066-1283.” Dissertations and Theses, Paper 5567, (2020), ii.

[53] Ibid, 2.

[54] Ibid, 15-16

[55] Ibid, 22.

[56] Ibid, 10-13

[57] Walter Map, De Nugis Curialium, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983), 183.

[58] Ibid, 145.

[59] Gerald, Description, 189.

[60] Map, Nugis, 1.

Leave a comment