Canada has no ancient buildings or monuments, no written records or large-scale conquering civilizations. Our history is not carved in stone. European nations and others in the Old World have long written histories, have seen the rise of large civilizations and have constructed large, ancient cities.

We are unique in another way. Our history is a more modest one of a vast, unspoiled freezing wilderness that had to be persevered through, had to be overcome, and this involved ambition, but also disappointments. This is one of the things that makes the history of Canada, and the New World in particular, very interesting.

The first people to arrive in Canada after the First Nations were the Vikings, whose ancestors had journeyed to Iceland from Norway. From Iceland, the Vikings headed west where Eric the Red reached and settled Greenland. A ferocious dauntless people, the Vikings were some of the best sailors in the world and searched the seas for food and adventure. On one such trip a sailor named Bjarni Herjolfsson was blown off his route while sailing between Iceland and Greenland. Herjolfsson glimpsed North America during a harsh wind and returned home to share its existence. Eric the Red’s son, Lief, attempted to find the unknown continent at around 1000 AD. The Viking sagas recount Lief’s extraordinary adventures and his discoveries of Helluland (Baffin Island), Markland (Labrador), and Vinland. The last location is believed to be Newfoundland, as hypothesized by the archaeologist Helge Ingstad when he discovered the remains of a Norse settlement in L’Anse aux Meadows in 1961.

According to the Norse sagas, Lief was blown away by the masses of salmon and lush grapes in Vinland. One year later, Lief’s brother Thorvald returned to North America to attempt to contact Vinland’s natives. But the legends say that Thorvald and his crew were assaulted by “Skraelings” with bows and arrows. Other tales say that the illegitimate daughter of Eric the Red, Freydis the Brave and cruel, defended the Vikings by running at the Skraelings and scaring them off with her fierce eyes and grinding teeth.

In the sagas, the Skraelings are described as dark-skinned people wearing their hair strangely. Historical anthropologists have guessed that they were Algonquians. Whoever they were, they drove off the Vikings from the mainland. But there is a possibility that the Vikings returned to the northern areas of the continent. The explorer Vihjalmun Stefanson described tall, blond “Copper Eskimos”, making some people believe that the Norse mixed with the Inuit in Baffin Island.

Later expeditions: The 15th century saw an unprecedented shift in mankind’s geographic knowledge. European kings and merchants dreamed of finding a way across the Atlantic to the Orient and its spices, jewels and silks. But Ottoman and Italian control of the routes to the Middle Eastern markets proved to be a frustrating obstacle. France, Spain, and soon England enviously looked west towards the “Sea of Darkness” (the Atlantic Ocean) and questioned whether they could reach the Orient from there or only the end of the world. Later upgrades in ship building techniques would allow such a venture to be realized.

Cabot and Cartier: Italian navigator John Cabot was the first adventurer to discover Canada and claim it in the name of a king. He was famed for his wild imagination and adventurous spirit. In 1496 he convinced King Henry VII to allow him to find a way to the Indies and claim it for England. On May 2, 1497, Cabot ventured away with 18 men on his ship The Matthew. After sailing for 52 exhausting days, Cabot found Cape Breton Island and disembarked there on June 24. Cabot then planted and raised the British flag, claiming the land for King Henry VII.

Although he did not find the gold that he had coveted, he found that the soil was very productive and that the climate was temperate and hospitable. He believed he had found the northeast coast of Asia, and that he would soon find the precious silks and gems that he covered so much. Cabot couldn’t find either of those but he did describe the abundant fish and timber.

When Cabot returned, Henry VII, expecting gold, was disappointed at hearing of only fish from the explorer and paid him £10 for his endeavors. The king wanted Cabot to try another adventure, and he did in 1498. This time, Cabot travelled to Baffin Island and Newfoundland. Cabot finally headed back to England and died there aged 48.

Many explorers then set out on Cabot’s footsteps but were unsuccessful until Jacques Cartier, at the behest of Francis I of France, set out for North America in 1534. His journey laid the foundation for French and British competition for mastery of the continent.

Cartier journeyed inland until he discovered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Believing that the river led to the Orient, he navigated up the St Lawrence until he arrived at the Iroquois villages of Hochelaga and Stadacona (the locations of modern Montreal and Quebec City respectively). Here the Indians were so nice and welcoming to Cartier that he took two to accompany him back to France. Francis I was also dissatisfied but Cartier appeased him by telling him that he had put up a cross in the king’s name at Gaspe Peninsula and named the land New France.

The Arctic ventures: 50 years after Cartier other explorers wished to find the Northwest Passage past the Americas. One of them was Martin Frobisher. Elizabeth I sent this swashbuckler to search for an iceless path to the Americas. Although Frobisher was not really important for British history, he has endured to this day as a folk hero. 300 years after Frobisher’s adventures, the adventurer Charles Hall found the relics of a structure constructed by Frobisher’s men. Hall wrote that in 1861, the native peoples talked about Frobisher as if he had recently been with them.

Another man attracted to adventure was Henry Hudson. He made many voyages to North America attempting to find a way to China, but his last one had a tragic end. In 1609 while at James Bay the Discovery froze in the ice, and the vessel and its crew headed into “winter quarters”.

After a long and harsh winter aboard the ship, Hudson had an altercation with a fellow crew member, John Greene, who ended up leading a mutiny with his fellow sailors. Hudson, along with his son and seven others loyal to him, was set adrift. Green later died in a clash with the Inuit and the others were imprisoned when they got to England. Henry Hudson’s fate is unknown.

After Hudson came Thomas James (1631) – who lent his name to James Bay – and wrote descriptively of his adventures in a travel journal called The Dangerous Voyages of Captain Thomas James. Coleridge’s renowned poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was inspired by this account. Later, the British naval officer Edward Parry travelled the farthest to the Northwest Passage when he got to Melville Island after pushing through the northern ice-bergs.

Perhaps the saddest and most distressing tale of all the adventurers is that of John Franklin, a British rear-admiral and explorer. In 1819 Franklin led an exploration to find a path from Hudson Bay to the Arctic Ocean. After his first trip succeeded he set out again in 1825, and in 1845 made a third trip to North America. He was confident he would discover the Northwest Passage. He was joined by a Captain Crozier who had voyaged with Edward Parry. His ships, Erebus and Terror, were never seen after July 26, 1845. Years later a rescue mission found their skeletal remains and a journal recounting the journey’s last days. Although John Franklin had only needed to travel a few miles more to succeed, exhaustion and exposure had claimed his life.

Only in 1906 would the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen successfully find the Northwest Passage where so many had failed over the centuries.

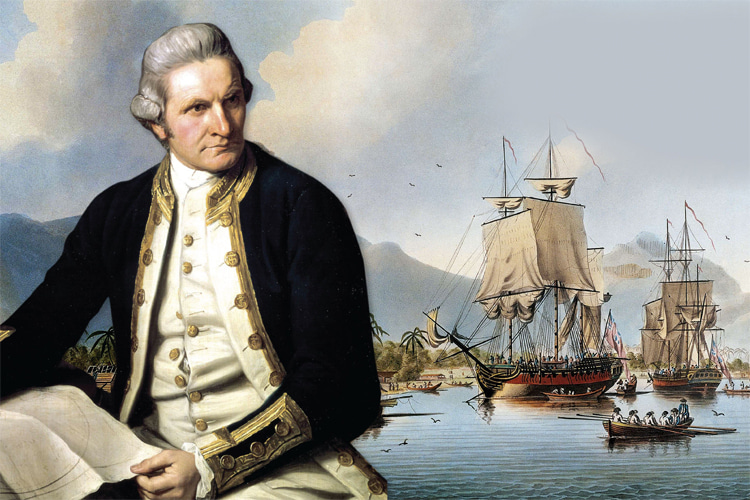

Exploring the West: The other side of Canada was another area that the Europeans were interested in. In 1778, Captain James Cook became the first European to step ashore on the Pacific Coast. He was searching for a waterway through North America starting in the west but later had to accept that it did not exist.

Later, George Vancouver found the outlet of the Bella Colla River. during his adventures in 1791-95. Seven weeks later, the ardent Scotsman Alexander Mackenzie ended up there as well. One of the reasons that adventurers travelled up the rivers of the West Coast was to hunt for furs.

The lack of gold and precious stones in Canada disappointed the English and French, but despite this they began to lay the foundation for their colonization of this area.

What excellent writings Diego. I enjoyed the refresher of the history I learned in school. Fascinating to read about and think of such a time when there were such brave adventurers discovering this world!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much Tracy, I’m glad you liked it!

LikeLike